Tesla: Elon, EVs, and Economics

History suggests discretion is the better part of valor

A ‘stupid’ idea.

That was how Musk reacted when Harold Rosen, a veteran in the space industry, suggested building electric drones to provide Internet service over lunch. Straubel, who would go on to become a co-founder of Tesla, quickly pivoted to the topic of electric cars using lithium-ion batteries.

Given how much battery technology had improved and his own abortive attempt - which lasted all of two days - at researching high-density energy storage at Stanford, Musk was immediately hooked, and thus the idea for Tesla was born.

‘I was going to work on high-density energy storage at Stanford. I was trying to think of what would have the most effect on the world, and energy storage along with electric vehicles were high on my list. Count me in.’

— Elon Musk, Tesla CEO

From the get-go, Musk understood that the key tech moat for EVs was the battery technology.

Musk’s interest sprung from the insight that batteries would soon store enough energy, at a price point low enough for consumer EVs. Uncoincidentally, BYD, now one of Tesla’s top competitors, started life as a battery company.

In the beginning, there was economics

Contrary to popular belief, EVs are not particularly new.

In the 1830s, decades before the first Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles had ever hit the road, the Scottish inventor Robert Anderson built a simple electric carriage.

Despite nearly two centuries of technological advancement, the core challenges for EVs - cost and battery capacity - ever since their inception have persisted to this day.

Depending on who you ask, other pioneers, such as the Dutch Stratingh and Becker, the American Davenport, the Hungarian Jedlik, etc., all have at least somewhat credible claims to have built the first electric vehicle.

Unfortunately, all those efforts suffered from the same flaws - high costs and short range, exacerbated by the fact that mass manufacturing technologies and rechargeable batteries had yet to be invented.

Consequently, electric vehicles struggled to make much headway against even horse-drawn carriages, let alone ICE automotives when they appeared on the scene. The only form to gain much traction was electric trams, which were bound by pylon and more often than not, track.

Having already successfully founded, scaled and sold multiple businesses, Musk knew the economic realities all too well.

Musk adopted the right skim-pricing strategy for rapidly progressing technologies - coming in at a premium price point, then lowering prices and raising volumes.

When he later visited AC Propulsion, another EV startup, and saw their impressive prototype called tzero, he immediately realized that their strategy to go with a cheaper, slower and generally less attractive car was not going to be successful.

‘Nobody is going to pay anywhere near that [$70,000] for something that looks like crap.’

— Elon Musk, Tesla CEO

Elon Musk’s business sense was correct: skim-pricing was clearly the better way to go. It worked well for technologies on the cusp of becoming viable, and the Roadster was the result.

If it looks like a car company…

Many detractors cite the lack of attractiveness of the automobile industry, even as proponents, perhaps indignant that Tesla should be put down as a mere car company, declare that it is in the ‘AI business’.

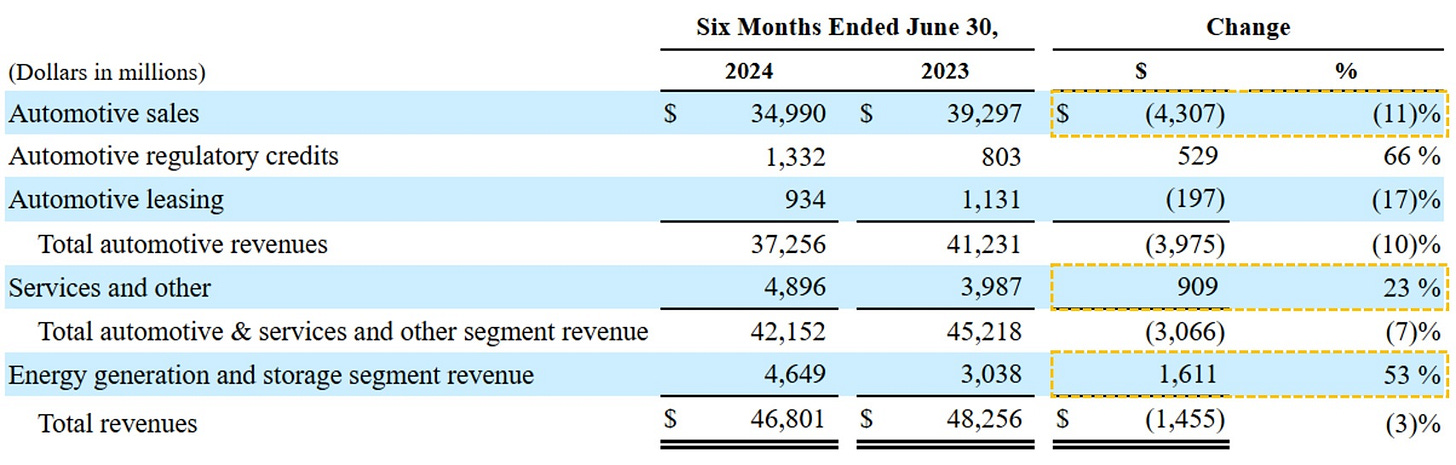

Going by the numbers though, automotive sales are the dominant contributor to sales.

Some 80% of Tesla revenues continue to be from car sales, which have been declining somewhat, even as energy generation and services revenues have risen.

In turn, well over 90% of Tesla’s automotive sales are coming from Model 3 and Model Y sales.

It must be said that Musk’s premium-first strategy worked brilliantly in Tesla’s first 15 years, despite frequently flirting with disaster when running into production hell and liquidity issues.

During the GFC, Musk even had to invest his personal funds into the company to keep it afloat.

But overall, the roadmap from the Roadster, through the Model S, Model X, and Model Y to the Model 3 was masterful. Musk was (just about) able to jump from one node to the next, scaling with extreme intensity.

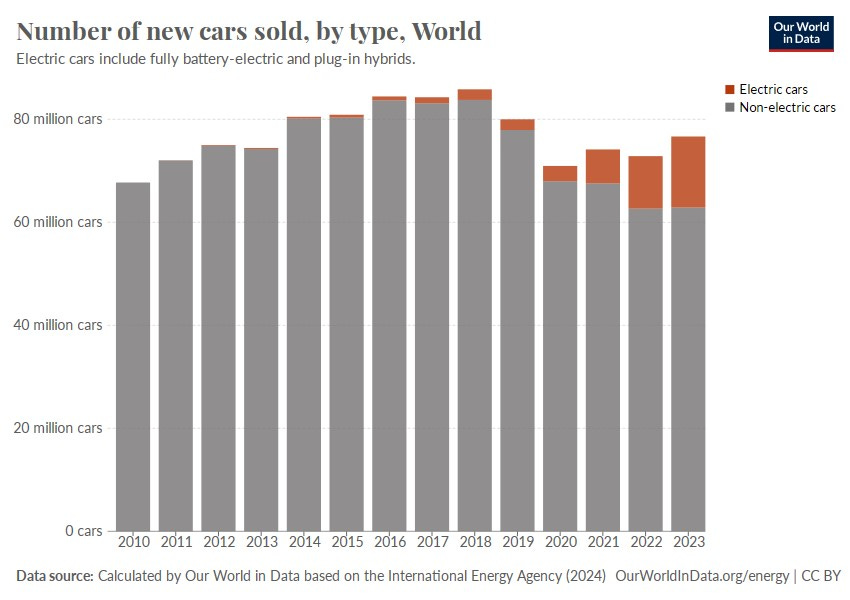

From the chart above, post-pandemic the number of cars sold has yet to reach the 2018 peak.

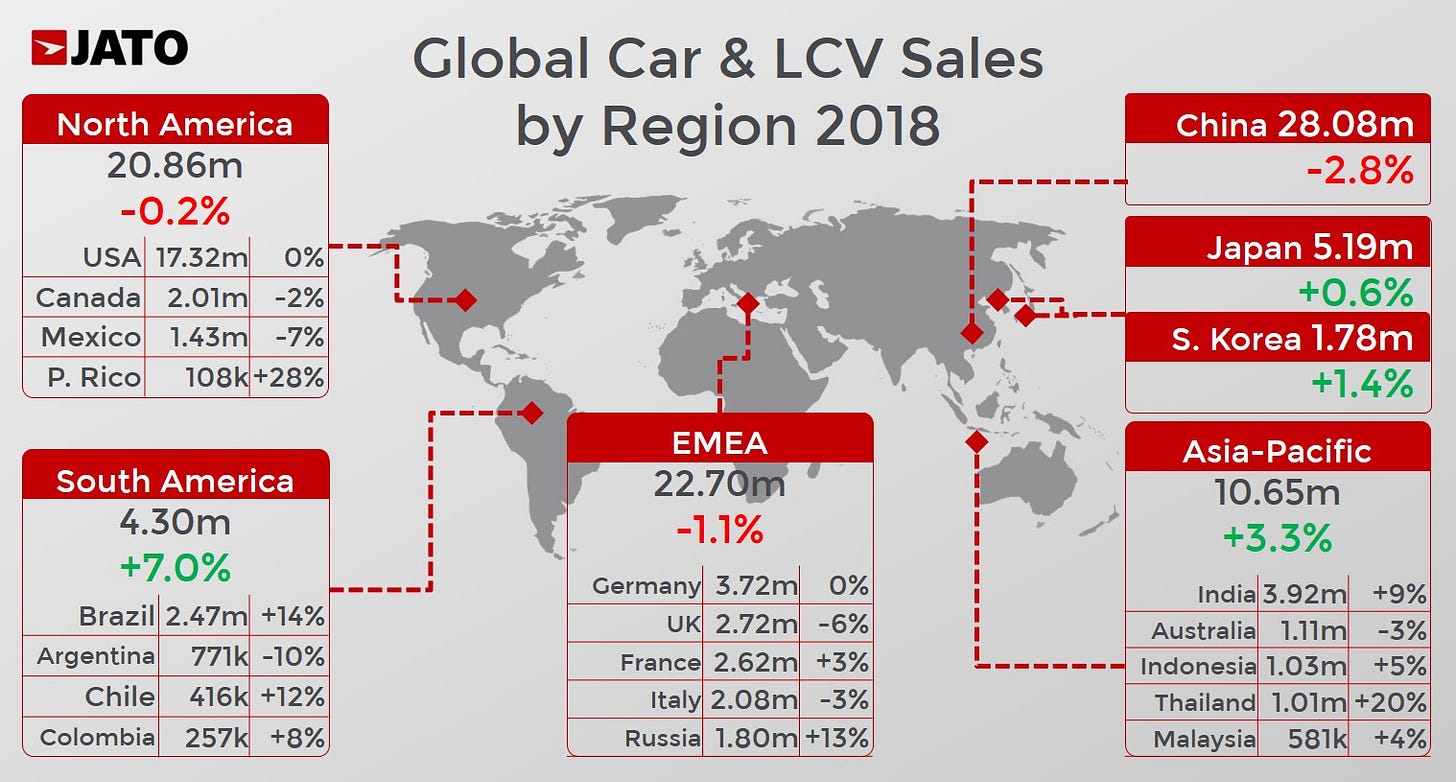

Zooming in, we also find that global car sales can be divided into 4 comparably sized regions, each buying around 20 million cars (slightly more if including light commercial vehicles like pickup trucks as in the map below):

China - largest market but declining sales at the overall automobile level

Europe - mature market, mostly stable sales

North America - mature market, mostly stable sales

Other (Japan, India and Brazil leading the way, followed by other SEA and LatAm states) - developed markets have stable sales, with LatAm and SEA still growing

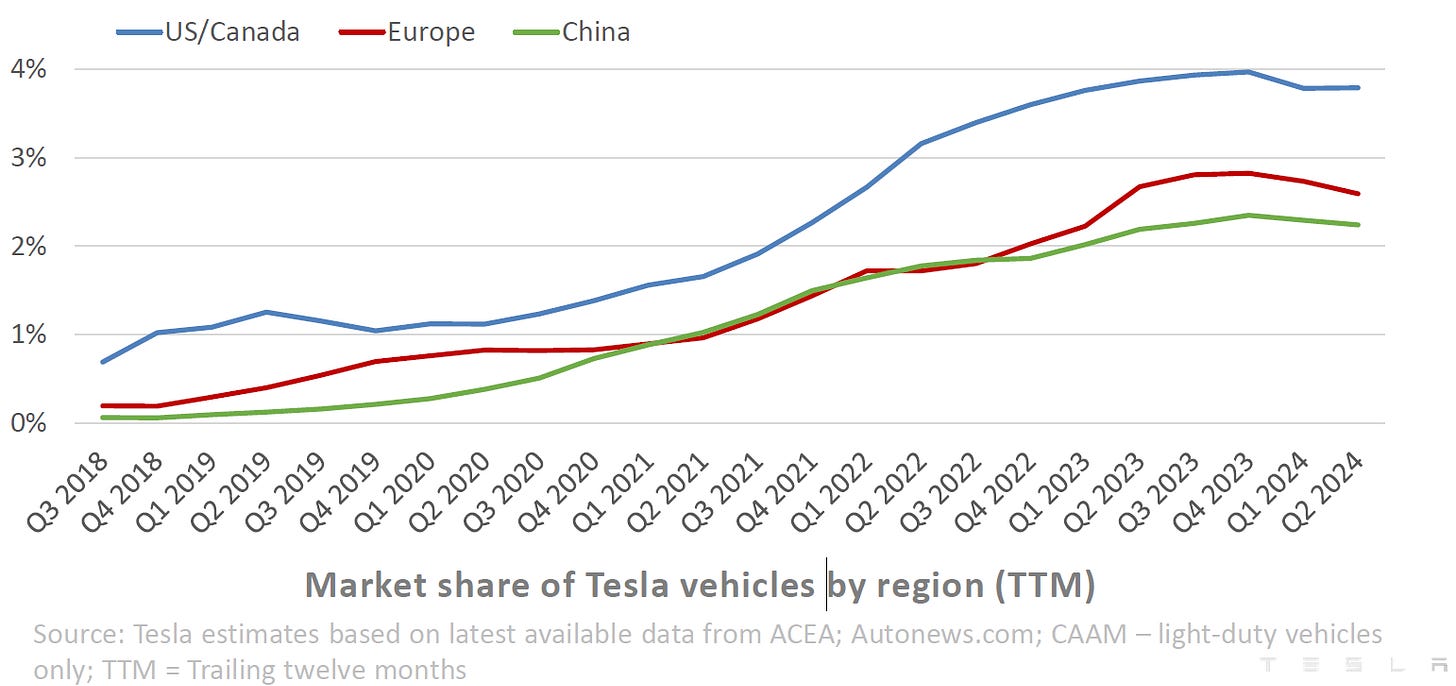

Consistent with its skim pricing strategy, Tesla’s market share is highest in North America, followed by Europe and then China. Together these three would constitute nearly 80% of the global market by volume, and more by value.

Unfortunately for Tesla fans and investors however, its share in all three major regions has been stagnant and declining since the end of 2023.

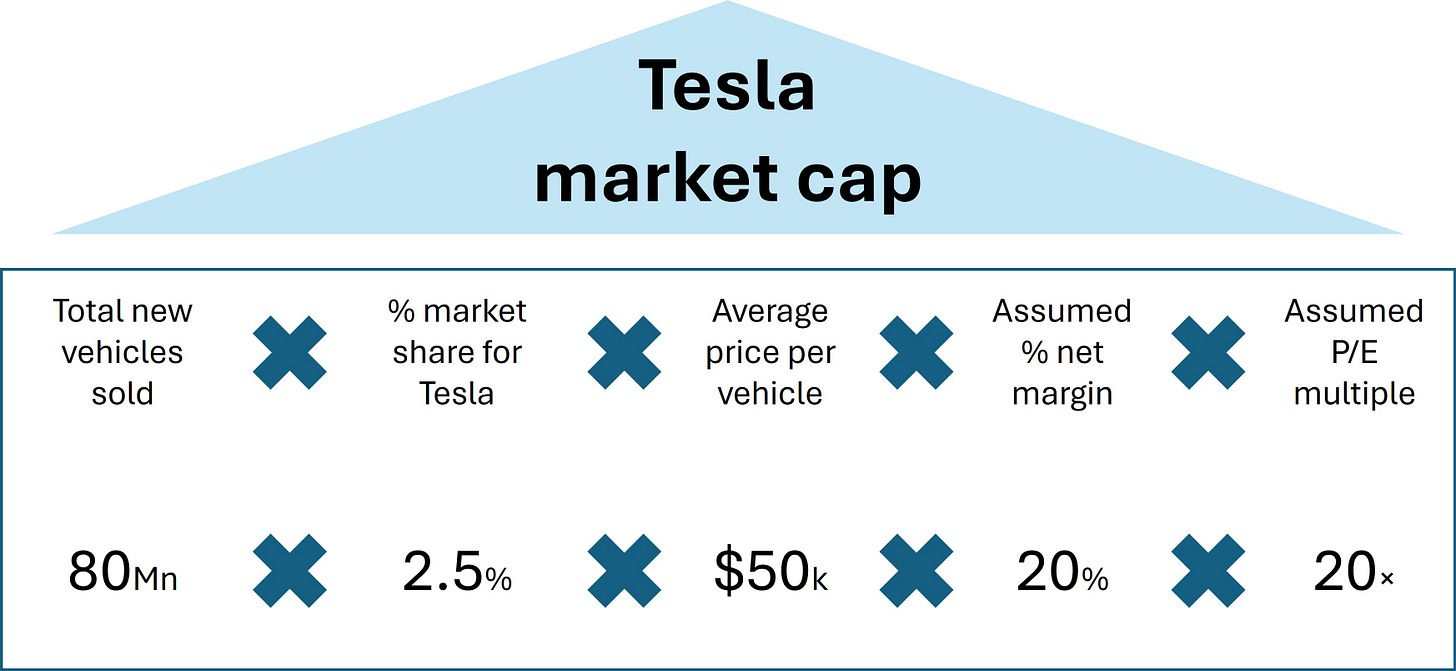

Note that Tesla’s 2023 deliveries came to 1.81 million units, which equates to around 2-2.5% of global share by volume. Already we can do a quick sense check of the potential market value of Tesla in say 5 years’ time:

Total new vehicles sold. With the cost-of-living challenges in multiple markets, and the real estate crisis in China, demand growth will likely remain soft, so we conservatively estimate 80 million.

% market share for Tesla. We optimistically assume 2.5% though market shares across top markets are already flattening or declining, and competition will likely increase.

Average price per vehicle. We assume that Tesla dominance in the US market will protect its margins, and ensure ASP of $50k - again quite optimistic, given that a Model 3 would start at just above $30k in China.

Assumed % net margin. Tesla used to enjoy higher net margins, which fell as the intense competition in China has taken hold - we assume it goes back up to 20%.

Assumed P/E multiple. Since Tesla will be much more mature, we assume its P/E multiple will also normalize, leading to around 10.

The final answer comes to $400 billion, a sharp contrast to the $724 billion market cap that Tesla commands today. If the rest of the business were to be worth $100 billion, that would still leave us over $200 billion below the current market cap.

Yet even to even realize the sales in the above estimate would involve overcoming significant geopolitical headwinds.

To understand why we need to dip again into history.

The ultimate son of Chimerica?

In 2011, Betty Liu from Bloomberg interviewed Elon Musk. She asked about his views on BYD, noting that Buffett had invested in the company.

Musk laughed gregariously and asked if she had seen their cars.

He had good reason to be skeptical. In those years, BYD was still better known as a manufacturer of electric buses than cars - and its HK-listed shares in the middle of massive drawdown well over 80%.

Musk’s views would change in due time. The Chinese auto market was appealing, and though import tariffs had been gradually lowered - with a change from 20% to 15% in 2018, to be truly competitive still required a local manufacturing presence.

Meanwhile, Tesla was suffering from painful capacity bottlenecks. Many had grown fond of mocking Musk’s delivery promises going up in smoke.

He had just the man for the job. The Shanghai-native Robin Ren, Musk’s friend from UPenn and previously CTO for Dell, successfully secured tax breaks and cheap loans to set up shop in Shanghai.

Towards the end of 2019, less than a year after breaking ground, the first production vehicles came out of the Shanghai Gigafactory.

Elon was thrilled.

‘China is super good at manufacturing, and the work ethic is incredible. If we consider different leagues of competitiveness at Tesla, we consider the Chinese league to be the most competitive.’

— Elon Musk, Tesla CEO

By 2021, China was producing over half of Tesla’s vehicles, and only one in four was sold in the Chinese market.

Much of the rest were bound for other Asian markets, and some for Europe. That year, The China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) found that over half of the EVs exported by China were produced in Giga Shanghai.

Tesla, which still relies on China for around 40% of its production, and recently broke ground on another plant in Shanghai, has significant exposure as one of the top exporters.

But nowadays, vehicles produced in China face a 100% import tariff in the US, and Tesla faces a 20.8% tariff if it sends them to the EU - on top of the 10% existing rate. Elsewhere, Brazil is also planning to increase tariffs.

The US tariffs would have limited impact on Tesla’s ability to maintain market share, since it already has the Fremont and Nevada plants, though it would prevent a potentially higher margin with the lower Chinese production costs.

Tariffs would also mean cars produced by Giga Shanghai would be largely restricted to China, elsewhere in Asia, or Europe.

The issue is that in all those destinations, Tesla will face strong competition from Chinese car brands such as BYD and SAIC, who are similarly constrained.

Playing in a smaller field means that price wars may easily ensue. This spells a major challenge for Tesla going forward.

Although Tesla has a clear edge in the US, Chinese brands have been growing strongly in China, and have also begun to ramp up exports into the rest of Asia and Europe. They are competitive on both price and quality.

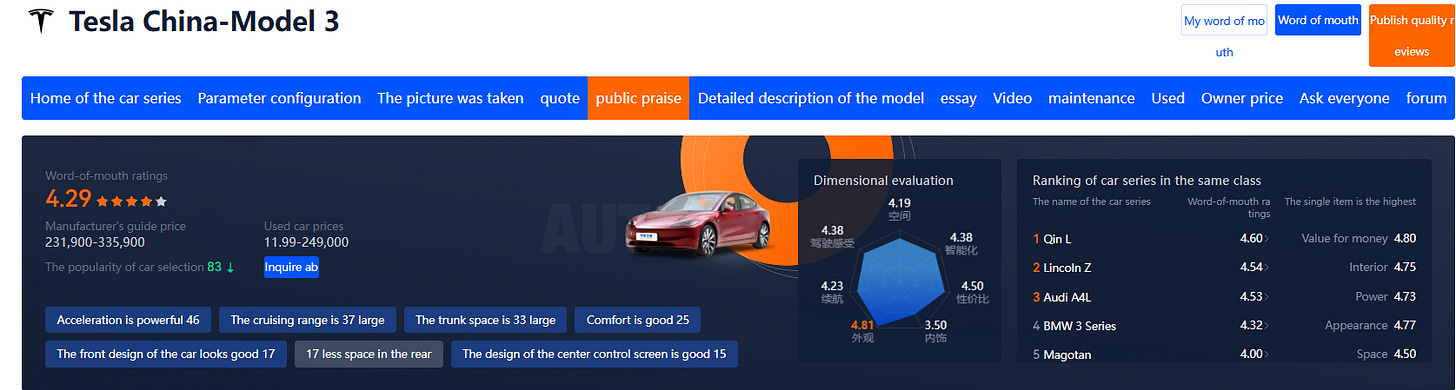

For example, on Autohome, the leading car review platform in China, Tesla’s model 3 received 4.29 stars out of 5. While reasonable, this came behind the Qin L from BYD, and the Lincoln Z from the JV Changan Ford.

Many users complained about build quality and various noises in the Tesla Model 3, even as they waxed lyrical about the much cheaper BYD Qin L, which started at under CN¥100k (around $13.7k), or less than half of what the Model 3 started at.

The premium-first skimming strategy has finally run into worthy rivals. Tesla has been relentless in its push to drive prices down and volumes up, while the likes of BYD started cheap and are now premiumizing.

The challenge is that they are starting to offer luxury propositions - at something like half the price of ICE alternatives.

Many markets are also hampered by their relative lack of charging infrastructure, limiting the size of the cake at any point, further intensifying competition for those that are open.

While Tesla had the first-mover advantage and was the first to enjoy economies of scale, BYD is already at a comparable size.

There are also plenty of competitors beyond BYD - the field is crowded with 10-15 competitive Chinese brands.

These have sought to compete on multiple fronts, including proprietary software that are better tailored to local user habits, premium materials for interiors, and an abundance of screens to serve hyper-digital Chinese customers.

Some innovations verged on the wacky, such as allowing front seats to pivot 180 degrees so everyone can get together to enjoy a game of poker, or even 43-inch screens … for passengers in the back.

Declining volumes and falling share, combined with price cuts to keep up in China spelt a difficult period for Tesla, though the worst of the price war appears to be over for now, with BMW, Mercedes-Benz and Audi all putting prices back up very recently.

Do Robotaxis dream of tax credits?

But what about the long-vaunted full self-driving (FSD)? Should that not add a huge boost to Tesla’s valuation? And what about its batteries, and services segments?

While it would be perhaps foolhardy to bet against Elon, discretion is probably the better part of valor. To address our views on FSD involves another detour into the mind of Elon Musk.

Elon’s mental frameworks have done wonders for Tesla. His role at the company is arguably bigger than even Ray Kroc’s in the success of McDonald’s. His minimalistic approach and penchant for removing unnecessary parts has been wildly successful.

‘Step one should be to question the requirements. Make them less wrong and dumb, because all requirements are somewhat wrong and dumb. And then delete, delete, delete.’

— Elon Musk, Tesla CEO

A celebrated anecdote involved Musk finding that a robot sticking strips of fiberglass to battery packs was constraining the throughput of the assembly line.

First, he blamed himself for trying to over-automate, since the robot was slow, kept dropping the fiberglass, and also went too heavy on the glue.

Then he asked the critical question - why those strips were necessary. The engineering team told him it was a requirement from the noise reduction team to limit vibration.

But then the noise reduction team said it was from the engineering team to limit the risk of fire.

Musk decided to record the noise both with and without those strips. It turned out that those made no tangible difference, so he had them removed altogether.

Of course, this empirical and subtractive mindset synergized extremely well with the premium-first approach, which meant cutting more and more parts.

Yet seems to have created what we believe may be a longer-term disadvantage for Tesla’s FSD.

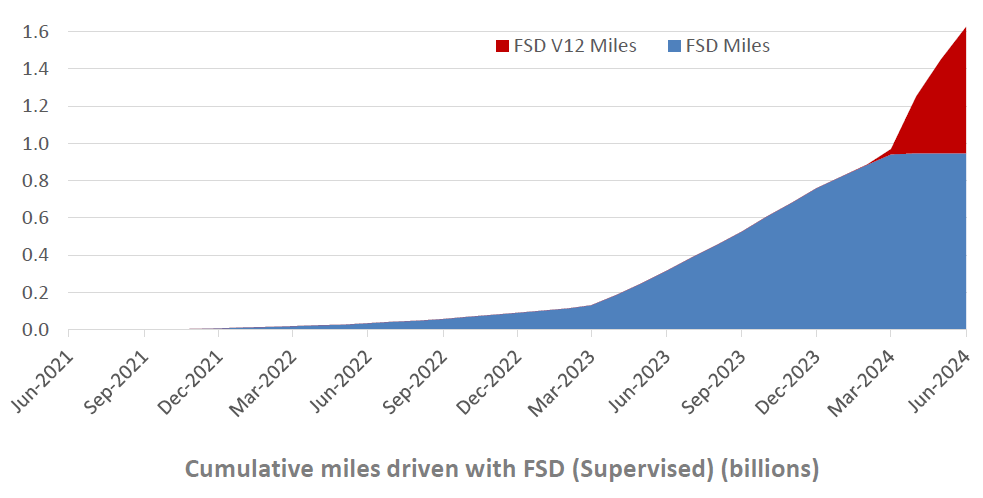

Long dismissed as vaporware by many media outlets, Tesla’s FSD took the market almost by surprise this year.

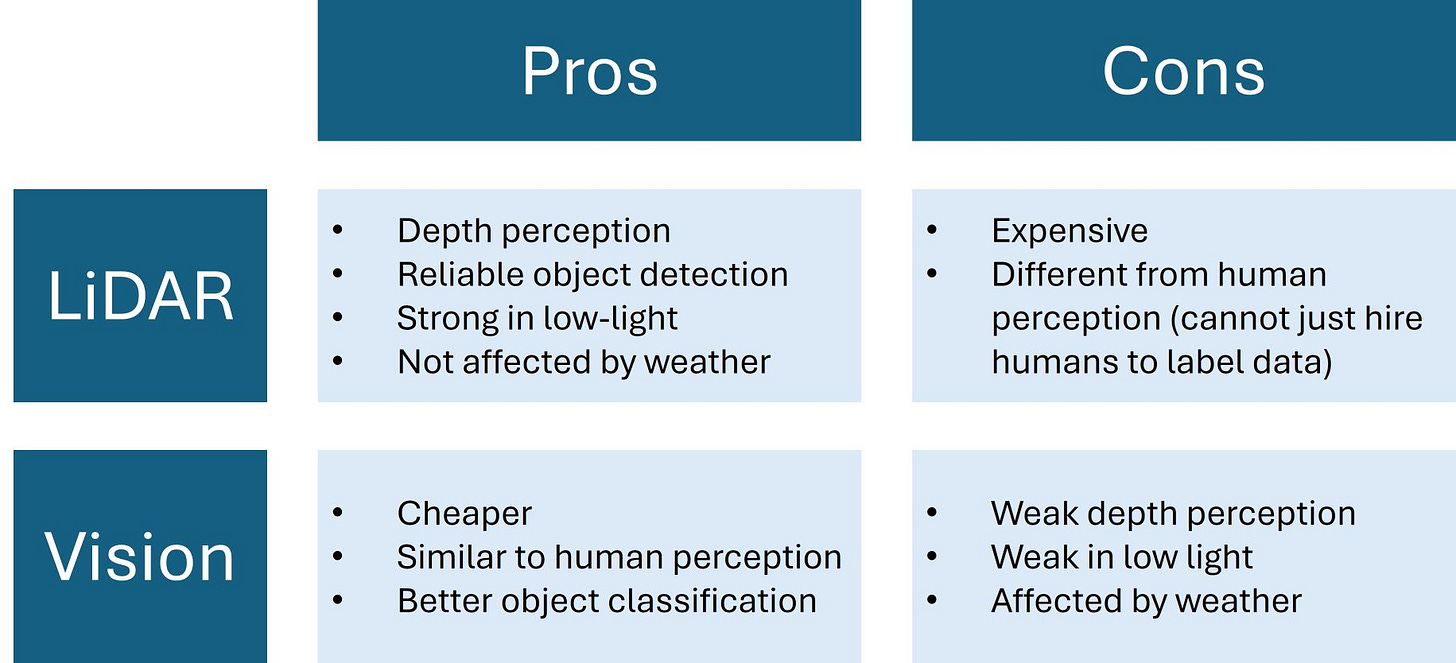

In fact, to reduce the cost of the vehicles, Musk had insisted that Tesla go ‘vision-only’, and not the hybrid LiDAR + vision route used by the likes of Waymo or Baidu.

The argument goes that since human drivers can drive with vision only, algorithms should be able to do the same. Importantly, going LiDAR-less means one less part and lower costs.

To enable sufficiently low prices, the removal of LiDAR was perhaps a necessary step for Tesla.

Talented Tesla ML engineers appear to have indeed largely solved the challenges of vision-only self-driving.

However, all this runs contrary to another important moat in the AI sector: data.

‘It’s worth trading a lower sticker price for the collection of valuable data.’

— Alpha Exponent

Humans indeed do not need LiDAR to drive. We also do not need wheels to run. Yet think of rear parking sonars - they can help us to be better at driving (or at least parking).

Competitors that do have LiDARs and can capture this data will be able to build safer self-driving systems. This would then be expressed in terms of reduced risk of accidents and litigation - and eventually, lower insurance costs.

Once scaled, this data moat becomes self-reinforcing; more market share means more cars on the road, more data captured, and better self-driving models.

Of course, this does not preclude the possibility of Tesla later adding LiDAR sensors to its vehicles. However, more R&D to utilize the 3D data captured, and integrating everything into the existing codebase and production pipeline would be necessary.

Incidentally, the number one LiDAR player, Hesai Technologies, which was founded in Silicon Valley but later relocated to Shanghai, is undergoing House scrutiny for national security concerns.

If Tesla is unable to use them and other Chinese providers, it may increase the cost and therefore elevate the decision threshold to adopt LiDAR.

To compound the issue, Tesla recently rolled out its FSD Beta software (V12, and now V12.5), which is an end-to-end system - a single model would be responsible for handling all inputs, and delivering all outputs.

Previously, multiple different systems were used for perception tasks such as object detection, lane recognition, and rule-based algorithms for planning and control.

Perception and prediction tasks are generally driven by machine learning, even as planning and control are coded using traditional algorithms.

Before the development of the single, end-to-end system, each of the components could still be changed and optimized more or less independently.

An end-to-end system changes the equation, again making it more expensive to add LiDAR to the mix afterwards.

This is not least because historical data would not contain LiDAR input - making it less relevant for any future systems equipped with LiDAR.

Of course, apart from all this, there are social and political costs that are associated with FSD.

Uber is a good reference. Its market cap is $133 billion, while its gross margins historically fluctuated between 30-40%.

If the human driver were to be removed, it is not difficult to envision a robotaxi company running at gross margins in excess of 50%, although a much more asset-heavy model is more likely (with company-owned vehicles rather than Uber’s high-margin software platform play).

Recall that Uber in its early days also faced significant barriers as previously licensed taxi drivers protested against their livelihood coming under threat.

Yet FSD would almost entirely remove the need for human drivers.

And if something goes wrong - Tesla would not even have gig drivers to shoulder the blame. Given the litigious nature of the US business environment, while related costs are uncertain, it would be dangerous to discount them entirely.

Both Waymo and Baidu have rolled out robotaxi services, and may provide further points of comparison in the future.

For the above reasons, it is difficult to imagine a Tesla FSD or even full-blown robotaxi service being worth much more in five years’ time than Uber today - or even north of $100 billion.

The situation is simultanously filled with conundrums and momentous implications.

Regulatory credits, the fastest-growing ‘revenue segment’ for Tesla in the past couple of quarters at 66% YoY, represent a transfer of wealth away from households to corporates.

Paradoxically, the rise of AI that would automate away jobs - there are around 1.5 million Uber drivers in the US - represents one of the fundamental arguments for Universal Basic Income (UBI), a movement for direct wealth transfers to households.

Profound socioeconomic and political impact may well limit the rate of adoption of FSD and robotaxi services.

A last word

So what about the other segments?

The aftermarket is also unlikely to prove to be the answer. EVs tend to be simpler machines than ICE vehicles, with lower maintenance costs, thereby constraining the size of the opportunity in services.

We would estimate this to be adding 10% to the auto segment market cap, roughly the same as the historical ratio of auto sales to services sales for Tesla (we accept that margins may be different, but this is just a simplification).

Meanwhile, even the most richly valued battery player, CATL, has only a market cap of around $100 billion. Tesla does not yet hold the same core technologies as CATL or even Panasonic, its long-time partner.

Putting all of the above together gives us:

Note that the above involve fairly optimistic assumptions in the innovation segments, which is still nearly $100 billion short of Tesla’s current market cap.

Nonetheless, we are not quite done yet.

Leasing and auto financing is a wholly different kettle of fish. Tesla does have an inherent advantage here thanks to its home market. For legacy automakers, financing is of course a core profit driver, though financializing like GE is a double-edged sword.

Whether Tesla can turn the financing and leasing segment into a core business, however, remains to be seen.

Though not without his share of controversies, Musk has been a force of nature in the sector. It would be difficult to bet against him.

But perhaps staying on the sidelines is the safer route.

We leave our readers with a reminder of how volatile the share prices of companies in emerging tech sectors can be - Chrysler’s share price took a rollercoaster ride in its first decade as a listed company.

Epilogue

It tends to be that in a bull cycle, the last to rise is the first to fall, as speculative capital flits across ever riskier sectors.

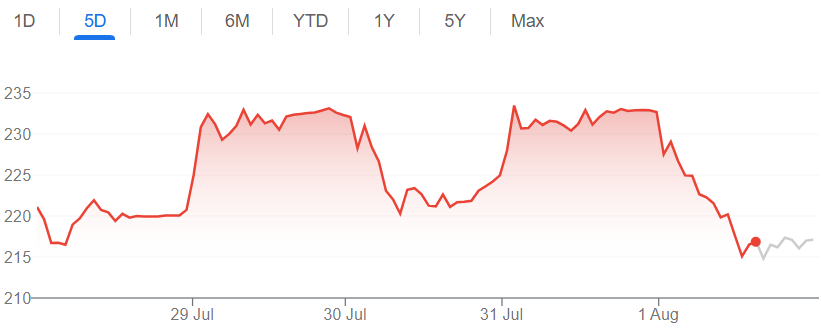

Tesla lost over 6.5% since its last trading session: the rollercoaster has started.

Full disclosure: This is not a solicitation to buy or sell. We have no current business relationships with the companies mentioned in this note, and are not paid to write this piece (other than paying fellow exponents of the research). We may buy or sell securities mentioned in this piece without explicit notice.

Disclaimer: This should not be construed as investment advice. Please do your own research or consult an independent financial advisor. Alpha Exponent is not a licensed investment advisor; any assertions in these articles are the opinions of the contributors.

What I find fascinating is that the man who realised earlier than anyone the cost of batteries could fall exponentially seemed to miss the fact that the same could happen to Lidar. Maybe back in 2016/17 when he made the decision to skip lidar, he genuinely expected to have (real) FSD in a timeframe where lidar wouldnt be cost competitive, but the reality is that today, that still doesn't exist, and a basic full Lidar suite from Chinese suppliers is ~1000RMB - clearly affordable and getting put on 20,000USD cars like Leapmotor's C10.

Love to see your insights on TSLA. How do you think about the current trends of SUV increases in NA? Seems GM's gaining market share and ford, stellantis is loosing it.