Word has it that there were only two investors who Charlie Munger would entrust with his money, and Warren Buffett was one of them.

This other man produced annualized returns exceeding 30% in the first decade since 1998, and nearly 20% over the two decades until 2017.

Most investors would jump at a chance to join the team at Berkshire.

But not this man. When Buffett and Munger asked him to be their successor and head up the investment team at Berkshire, he said no.

‘…he would prefer to be where he was. In effect he didn't want the job.’

— Warren Buffett

‘He so liked being a principal instead of being an agent working for somebody else. That was immediately obvious to me and, of course, that’s how I am. So, I naturally had considerable sympathy for him. I tried to get him to work at Berkshire, but I was fighting against nature.’

— Charlie Munger

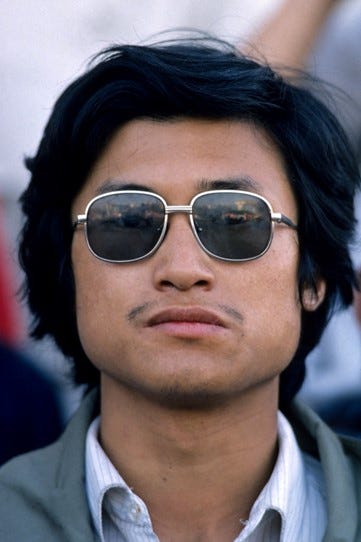

He, of course, is Li Lu.

Virtually penniless and not speaking a word of English, Li Lu arrived in the United States in late 1989, at the age of twenty-three.

He was given a hero’s welcome.

Just months before, he had fled Beijing for France, via an old smuggling route in Hong Kong. The ‘deputy commander’ of the student protesters, he decided to marry his girlfriend on the spur of the moment, to the cheers of other students.

Two decades before that, in 1966, on the eve of the Cultural Revolution, Li Lu was born in Tangshan, an industrial city in Northern China.

Li Lu’s parents and grandparents lost their personal freedoms soon after for being intellectuals. His grandfather was to die in imprisonment, though Li Lu only learned of his existence at the age of twelve.

When Li Lu was only nine months old, his father, an engineer, was sent to a coalmine to be ‘re-educated’, while his mother was sent to a labor camp.

Subsequently, he spent much of his childhood being shuttled from one foster family to another, the fleetingly adopted child of peasants and coalminers, before finally settling down with the family of an illiterate coalminer in his hometown of Tangshan.

In 1976, at the age of ten, Li Lu was finally reunited with his parents and two brothers. They survived the Tangshan earthquake that was to claim over 240,000 lives.

The coalminer’s family, however, did not.

Many other friends died in the earthquake, and Li Lu sank into a deep depression. He became disengaged, and frequently engaged in street fights.

However, his grandmother told him that while he had a sense of justice, real fights could not be won with brawn alone, but required the use of the brain, so that education was the only way to achieve justice.

‘I was careful not to be influenced by emotions that I know are poisonous and counter-productive to the journey I want to take; things like envy, resentment, hatred, jealousy, greed and self-pity. I certainly wasn’t born with immunity to this side of human nature. In fact, my early life experiences may require me to work even harder than others to guard against these human vulnerabilities.’

— Li Lu

Li Lu also learned of his grandfather, who received his PhD from Columbia University. He was fascinated by this man who he never had the chance to meet, and read his writings extensively.

Motivated by these events, Li Lu went on to read Physics at the prestigious Nanjing University, later transferring to Economics.

After hotfooting out of China, Li Lu knew he still had to finish his education. Columbia University was a natural choice, given its connection with his grandfather.

So here he was.

In his first weeks in the US, he struggled to adapt to American cuisine, constantly throwing up. He craved tofu, the ‘blandest food’ he could think of, which he felt he might be able to keep down.

He was in good company though. Human rights activists such as Mary Daly, who organized benefit rock concerts, introduced him to acts like Sting and Peter Gabriel, and Robert L. Berstein, the former chairman of Random House, the publishing house, and former chairman of Human Rights Watch.

Meanwhile Jason Epstein, the editor of Random House, took him to dine at a Chinatown restaurant.

After enrolment at Columbia, Li Lu’s first challenge was to learn English at summer school, where others thought he would fail. He did not.

He also found and took his grandfather’s thesis from the university library, deciding that he could take better care of it.

Like many other students burdened with college loans, Li Lu was on the constant lookout for two things: money and food.

One day, a fellow student gave him a flyer. A wealthy guest lecturer was coming to give a speech about making money.

Li Lu decided to go after noticing on the flyer that a buffet was offered - not uncommon for other events of the time.

When he arrived in the classroom however, he noticed that the long tables that would typically serve buffets were missing. Where’s lunch?

He asked his classmate where the food was, and the classmate told him that was the speaker’s name.

‘Since this guy dared to call himself “Mr Free Lunch”, I reckoned he must know something, so I sat down and listened. After a while, I felt suddenly what he was saying was far better than a free lunch.’

— Li Lu

Before, Li Lu was under the impression that stock traders were cons or gamblers. But what Mr Free Lunch said intuitively made sense. His principles were clear and easy to understand, and Li Lu first felt the draw of investing.

As it turns out, Li Lu - still picking up the English language then - had missed the extra ‘t’ in the speaker’s name. He had stumbled on to a speech by none other than Warren Buffett, and the stock market was to witness the rapid rise of a new philosopher-investor.

First, though, Li Lu had more to learn. Immediately after the lecture, he made a beeline for the library to study more of Buffett’s teachings, starting from P/E and P/B ratios, making extensive use of Value Line, a subscription research service.

However, Li Lu realized that for the first batch of companies he looked at, he did not understand their businesses well enough, only that they did not seem to be losing money.

Deciding to visit a few companies near New York to kick the proverbial tires, Li Lu saw for himself that they were real going concerns. Only then did he muster enough confidence to buy those stocks.

He improved his methodology by more carefully researching and understanding the businesses that the stocks represented. The more he studied, the more confident he grew.

By buying stocks, he also felt that he became a part owner of the underlying companies, which drove him to study those companies even more deeply. This became a self-reinforcing virtuous cycle.

Around this time, Li Lu was offered a book deal to write about his experiences, the proceeds of which he plowed into the stock market.

Soon, he felt he had enough to retire.

He had racked up $125,000 in the stock market, while the average annual salary in China at the time was around $800 - not that he could immediately head back, still being on the most wanted list.

But for Li Lu, this was only the beginning. He clerked for a District judge, then interned at a law firm, before interning with Allen & Company, an investment firm.

After six years as a student at Columbia University, Li Lu became the first student to simultaneously graduate with three degrees: a bachelor’s in Economics, an MBA and a JD in 1996.

This feat added to his celebrity, and he was invited to give a speech at the graduation ceremony. The New Yorker penned a short profile of Li Lu aptly named ‘The Graduate’.

Due to his various achievements, Li Lu had his pick of offers, and decided to start in investment banking with Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette (later acquired by Credit Suisse) in 1996.

On a fateful flight from San Francisco to New York, he came across Rena Shulsky, a New-York based real estate mogul, whom he met previously while giving a lecture.

She saw his potential and gave him $2 million in seed money. Very soon, he quit to start his own firm, Himalaya Capital Investment, in 1997. Celebrated investors such as Jerome Kohlberg - the first ‘K’ in KKR - lined up to put in their money.

Li Lu’s fund focused on opportunities in China, which was experiencing a growth boom.

It proved to be a disaster in its first year.

The fund suffered a loss of 19% amid the Asian Financial Crisis. To put this in context, the booming US large caps returned 31% in 1997 and nearly 27% in 1998. To US investors, it would appear as if Li Lu had underperformed by close to 50%.

A major investor withdrew his funds, and Li Lu was under pressure; his one-man shop, like many others before it, was in danger of folding.

However, in 1999, Li Lu made back his investors’ money - and then some, partially thanks to the emerging markets enjoying a great year with over 57% returns, outpacing the still buoyant US large caps, which returned nearly 20% that year.

Li Lu proceeded to try his hand in venture investment in 2000, before Julian Robertson, the famed founder of Tiger Global Management, and subsequent godfather of the Tiger cubs, made him an offer he found difficult to turn down in 2002.

Robertson demanded that Li Lu take short positions. Robertson’s preferred style at Tiger was long-short equity, which took both long and short positions in equities, thereby providing hedging and reduced portfolio volatility.

It had the added advantages of potentially magnifying gains - either if both positions gain, or by acting as cheaper leverage if short positions burn money more slowly than a direct loan, as well as being less dependent on the vagaries of the broader market.

Unfortunately, this was not Li Lu’s game. The long-short strategy had a far shorter time horizon than what Li Lu was used to. He found this to be another highly stressful period, and went back to his long-only strategy.

The next year Li Lu was invited to the home of another human rights activist for Thanksgiving. Her husband was named Olson, a director for Berkshire Hathaway. As it turns out, a certain Mr Munger was also present.

The two started to talk about stocks, and kept talking about stocks late into the evening.

Much impressed by Li Lu’s intellect and drive, Munger gave him $88 million to manage in 2004, when Li Lu raised a new fund.

‘I've read Barron's for 50 years. In 50 years, I found one investment opportunity in Barron's, out of which I made about $80 million. For almost no risk. I took the $80 million and gave it to Li Lu, who turned it into $400 million or $500 million.’

— Charlie Munger

Munger mentioned the above in the Daily Journal Annual Meeting in 2017 - and his net worth was estimated to be $1.1 billion in 2014 by Forbes. Yet the WSJ reported in 2010 that Li Lu’s own $40 million had turned into $400 million, while Berkshire’s $230 million in 2018 had turned into $1.2 billion. This meant in just six years, by 2010, Li Lu probably made over half of Munger’s fortune, with annualized returns of over 30%.

From the one idea inspired by Barron’s in his five decades of reading, Munger made the money that would turn into over half his net worth in under one-eighth the time.

Why has Li Lu been so successful? Munger attributes part of Li Lu’s edge to where he invests - China.

“And the rest of us are like cod fisherman who are trying to catch cod where the fish have been fished out,” he said. “It doesn’t matter how much you work when there’s that much competition.”

— Charlie Munger

Subsequently, Li Lu also introduced BYD to Munger and Buffett, setting up a famous trade that turned Berkshire’s initial investment of $225 million into $8 or 9 billion by 2023.

"Charlie is the one who got us in with BYD. That was his idea. He pushed it and I got to know Li Lu, and Li Lu is the one who brought us the idea. He's a very smart man."

— Warren Buffett

Takeaways

Summing up Li Lu’s core investment philosophy, we find that it is highly similar to Buffett:

Circle of competency

Focus on business fundamentals, not on price action

Bets on China - less competition for the fish

Long-only rather on long-short for more comfortable, longer time horizon

Concentrated bets, few trades

Tight-aggressive style as for poker - he rarely trades, but then ‘backs up the truck’ when he does

Total trading costs lower - these add up

Intense curiosity and searches for great businesses, not just commonly accepted mega caps or Buffett trades

Growth at fair value

Great businesses compound - remember, Li Lu has a very long investment time horizon

Good prices - Li Lu buys only when they are selling at good prices

Li Lu’s investment style evolved over time. From the original Graham-endorsed ‘cigar-butt’ philosophy and focus on P/E and P/B ratios, Li Lu shifted to prefer ‘growth at fair value’, much like Buffett, and buying excellent businesses at good prices.

‘I started out looking for cheap securities... Over time, I really fell in love with strong businesses. I morphed into finding strong businesses at bargain prices. I still have a streak in me that favors finding really cheap securities - I just can’t help it. But over time, I’ve become more attracted to looking for great businesses that are inherently superior, more competitive, easier to predict, and with strong management teams.’

— Li Lu

What has remained unchanged, however, is Li Lu’s focus on understanding the business and seeing himself as the owner. For this, thorough research and understanding of the core competitive factors are necessary.

We specialize in deep research into companies and their industries, also focusing on businesses with China exposure - just like Li Lu. We too hope to find that one idea to make all the difference.

Disclaimer: This should not be construed as investment advice. Please do your own research or consult an independent financial advisor. Alpha Exponent is not a licensed investment advisor; any assertions in these articles are the opinions of the contributors