Why not NVDA?

The bear bites

Amid the market euphoria for NVDA (no market cap seems too high), we issue a note of caution.

Nvidia's market cap is closing on $2 Tn. Now if we look forward 10 years and assume: 1) it has reached a terminal state where growth has slowed down, 2) valuation at 20X P/E; 3) operating at 30% net margins. All this implies revenues would need to be at around $333 Bn. Is that reasonable? Let’s see.

Source: MicroMacro.me

Nvidia has really tapped into 3 major growth trends (the above chart shows the revenue segments avove):

Gaming

Cryptocurrencies

AI & high-performance / general-purpose computing

We assess each in turn to see if they can help us come to that $333 Bn figure.

Gaming

Gaming hardware segments. Gaming software is only about a $200 Bn market, and hardware probably quite similar. These can largely be split into console, PC, mobile and peripherals. Peripherals don’t generally have GPUs, and:

PC. Nvidia has the lion’s share of the PC market, AMD with the rest.

Console. Nvidia has the Switch, but AMD has Xbox and PlayStation (and some other more niche consoles), and this is unlikely to change any time soon due to their need for a more powerful SoC.

Mobile & other. Qualcomm, MediaTek, etc., have their in-house designs or collaborate with specialist mobile GPU designers. Apple’s AR devices are likely to constitute a sizeable chunk of future AR/VR/XR/YR/ZR… but they are probably going to go with their own chips.

Will likely have to rely more on price increases than volume for gaming.

PC shipments have been stagnant for years, and similarly for console. Nvidia does not yet have competitive offerings for mobile (and appears to have redirected its SoCs to focus on EVs) or AR/VR. Long story short, this segment will likely have to primarily rely on price increases for growth.

There are some wild projections out there saying that gaming GPUs will grow at 30% CAGR, etc., but it’s probably safer to assume that gaming software will grow at sub-10% CAGR and hardware growth will largely be in line with that. Gamers buy hardware to play specific titles, so it does not make sense (apart from a few hardware enthusiasts) for hardware spending to far outstrip software spending.

Despite AI reducing the cost of content creation, the cost of creating the best content will not be significantly reduced – the best talent would attract even more pay, not less. However, there will be some overlap with AI below, and likely a significant boom when games start to employ large-scale LLMs (Large Language Models).

More intensive applications will likely shift to the cloud via gaming subscription services (which Nvidia GeForce Now also plays in), unless much more compute-efficient, reduced-size models are developed for edge computing – in which progress has been promising so far, except that Nvidia will need to be in the Goldilocks zone, and that there will be challengers (as explained later).

$30-35 Bn in 2034 from gaming as the base case, $50-100 Bn in an off chance.

Due to the above, and assuming Nvidia’s gaming GPU revenues have 10% CAGR – starting from ~$10 Bn, they’ll end up at $25-30 Bn in around a decade. Revenues from Prosumers and content creators (including computer graphics developers, designers, technical artists, etc.) historically stood at 15-25% that of content consumers, so $30-35 Bn seems reasonable.

An edge computing boom can potentially change these figures drastically, but too-efficient LLMs could also mean that the mobile devices (with no Nvidia GPUs) will be able to handle them. So really, Nvidia needs the Goldilocks LLMs: too large for mobile devices to handle, but small enough for PCs. In the off chance this happens, $50-100 Bn might be feasible.

Cryptocurrencies

Segment revenues are strongly tied to crypto prices and mining demand. Because of the proliferation of ASICs (Application Specific Integrated Circuits) however, GPU mining has fallen out of favor.

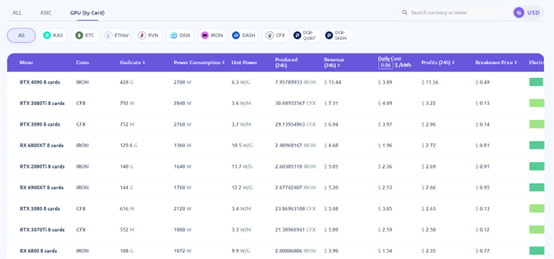

A few (ASIC-resistant) tokens can still be mined with GPUs, but they mostly have extremely low market caps, especially now that Ethereum has shifted to proof-of-stake, and can no longer be mined. One of the largest would be Conflux, sitting just under $1 Bn, with others such as Raven Coin in the low hundreds of millions.

According to F2pool above, 4090 & IRON appears to be one of the rare profitable ones, yet IRON’s market cap is negligible.

Indeed, many companies are shifting from crypto mining to AI, e.g., Hive Digital Technologies and Cambrian AI.

It is possible that a renewed surge in crypto prices will propel a new round of GPU shortages, to mine altcoins, but this hardly seems sustainable given its very boom and bust nature.

We expect limited crypto demand – less than $5 Bn annualized by 2034.

Altogether we would expect less than $5 Bn annualized revenue (when spread out over the years) from this segment within a decade, and during the crypto winters, there could be significant cannibalization with the AI segment.

AI & high performance / general-purpose computing

There are possibly a few different segments here, but we group together both public and private cloud – thinking of them as basically data centers for enterprise usage.

This is a tricky segment to forecast, but let us base estimates on servers. Gartner estimated global end-user spending on servers in 2023 to be $126.9 Bn, and forecasted single-digit growth through to 2027.

Even assuming a more optimistic 10% CAGR through to 2034, that would come out to be only $330 Bn – which would be under $300 Bn after accounting for manufacturing margins.

We expect a server GPU market in the neighborhood of ~$100 Bn by 2034, but believe Nvidia will be unlikely to capture it all.

Allocating a generous 30% of this to GPUs would provide a market of $100 Bn. Remember, the CPUs, memory, motherboards, and other components such as the power supply, chassis, network cards, etc., still need to be accounted for.

In some sense, due to its current dominant position, this is also Nvidia’s market to lose. We believe that within the next decade, viable alternatives may emerge to Nvidia’s GPUs, and so they are unlikely to capture the entirety of this $100 Bn market.

The most recent surge(s) in demand for AI hardware stemmed from software, specifically OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Sora, which are examples of generative AI technologies. These are powered by LLMs, initially created when Google engineers introduced the transformer architecture (no, not the Stanley transformer) in 2017.

This is because of the emergence of credible alternatives to GPUs like Groq.

Ironically, scant days before Nvidia released its stellar FY23 results (with revenues up 126% YoY and GAAP EPS up 586%), a key challenger, Groq, released its own accelerator card, which it calls the LPU (Language Processing Unit).

Source: Artificialanalysis.ai

For only $20 k, an LPU can output hundreds of tokens per second, and offer competitive performance vs an H100, which costs twice as much. As can be seen in the comparisons above, Groq has a considerable lead in both throughput and value.

Groq claims 5-10X speed up vs other cloud providers that use Nvidia chips. While exact performance in a fair head-to-head is unclear – being dependent on multiple factors, including actual model, context length and precision of quantization, it does show that Nvidia will have to overcome significant competition to take the entire market. LPUs use entirely different technology to GPUs, and offer a glimpse of potential substitutes.

Such alternatives approaches may shift complexity to software, lowering the barriers for hardware and thereby allowing more hardware competitors.

Limiting the depth for such a quick note, Groq’s novel approach shifts the complexity from hardware to software, a similar mindset to RISC (reduced instruction set computer).

This abstraction represents an important shift of the moat for hardware vendors. No longer will the processor hardware be handling all the optimizations for faster execution; the compiler software – and potentially customized optimizations for each model – will do the heavy lifting, and hardware can be simplified.

Of course, Nvidia is no slouch on the software front, with its mature CUDA stack, and continual TensorRT improvements, aimed specifically at deep learning & LLMs. However, the reduced coupling between hardware and software does open the door for many more competitors, including the elephant in the room – China.

Chinese firms have the motivation & fabrication processes needed to create indigenous substitutes, putting one-sixth of Nvidia sales at risk.

Source: Nvidia

As late as 2021, China revenues exceeded that of US revenues for Nvidia as in the image above, though all the figures above are for board partners, and not the end users.

Chinese companies have proven adept at designing chips but were hamstrung by sanctions and lack of access to the latest fab processes. However, Groq’s LPU is quite likely built on the older 14nm process – its marketing manager claims that it leaves “modern GPUs built on 7nm and 5 nm processes in the dust” and China’s SMIC has these capabilities.

Meanwhile, a good one-sixth of Nvidia’s FY23 revenues came from China, not even accounting for any indirect sales via third countries. Nvidia may find it extremely challenging to defend share once Chinese firms are able to advance their own solutions, perhaps following a similar route to Groq that circumvents the need for the latest fab processes.

Competitors have already made significant advances in creating software substitutes for the CUDA stack, a key part of Nvidia’s tech moat.

Furthermore, due to existing restrictions, Chinese engineers have already been forced to develop their own substitute for the CUDA stack, so the software side has made significant progress. The prime contender is Huawei’s CANN (Compute Architecture for Neural Networks), which now offers comparable capabilities to CUDA + CuDNN (CUDA Deep Neural Network), thanks to Chinese customers who have been forced to switch to local suppliers.

Meanwhile, Nvidia’s chief rival AMD is working hard on its own alternative to CUDA, named ROCm. An important part of stack is the HIP (Heterogeneous-compute Interface for Portability), with a tool called HIPIFY that can convert CUDA code to HIP code. Currently it has its share of glitches, but if it can gain sufficient traction to reach maturity, this would mark a significant threat to the formidable CUDA moat, by substantially lowering switching costs.

Intel is somewhat behind AMD in the race, and betting on its own alternative to CUDA, SYCL, to take off. Unfortunately, it seems to have gained limited adoption so far. Intel’s next fab process is also a big bet.

Other startups in the space such as Tenstorrent, led by the renowned chip designer Jim Keller, are also developing their own alternative to CUDA. Tenstorrent is open-sourcing its solution called Metalium.

Hardware from both Huawei and AMD are increasingly competitive, and Nvidia is already losing share in the China market.

Nvidia was previously dominant in the Chinese market with around 90% of the market; when Huawei tried to challenge with the Ascend 910 in 2019, it failed to gain any traction even within China.

However, due to multiple rounds of export controls, the less powerful chips that Nvidia has specially developed for China are starting to lose ground.

Huawei’s Ascend 910B is already on par, at least on paper, with the H20, the most powerful of Nvidia’s China-specific chips. These are only at the level of A100, and less than half as powerful as the H100.

However, the Ascend 910B has reached the market before the H20, winning an order for 1,600 chips in 200 servers from Baidu last August - an order worth over $60 Mn according to the SCMP. Meanwhile, H20 has only begun to take orders in 2024.

AMD launched its “AI Chip,” the M1300X, in December last year, which compares well against Nvidia’s flagship H100, as shown in the screenshot below. Of course, Nvidia will hardly stand still and will be ready with its H200 in Q2 2024. Nonetheless, we posit that there is a good chance that AMD be competitive in the enterprise market.

Source: AMD

In the meantime, the main challenges for LLMs are memory size and bandwidth. Normal graphics cards have high bandwidth VRAM (video random-access memory), but limited size due to the price tag. Meanwhile your standard computer RAM (random access memory) is cheaper but has lower bandwidth.

Startups in the space have yet to strike the right balance, with many having insufficient memory.

However, both AMD and Tenstorrent are using more scalable chiplet-based designs, and powerful interconnect technologies, which may give them a head start in this area. The image below shows the difference between a monolithic GPU, which Nvidia has, versus a chiplet-based design, which is what AMD and Tenstorrent use.

Source: PC Perspective

The trend towards MoE (Mixture of Experts) LLMs may advantage chiplet-based designs, in which AMD & Tenstorrent have the edge over Nvidia.

Nvidia’s approach with large single chips, and inter-GPU connections with NVLink lends itself well to model parallelism, which divides one model across different chips.

However, the latest generation LLMs have been trending towards MOEs, for example the open-source Mixtral 8x7B and the Camelidae-8x34B, chiplet-based designs may be the way to go in the longer term.

These better enable task parallelism, which refers to running different tasks at the same time, especially if the trend will be towards mixtures of heterogeneous experts (which we define to be mixtures of different model architectures), and custom, model-specific optimizations.

Nvidia themselves actually published a paper concluding that they believed in the superiority of a chiplet-based design in 2017.

What is next for Nvidia – any other drivers?

Nvidia’s next big bet appears to be on automobiles. It is relatively easy to put together a bull case: 1) after work and home, we spend the most amount of time on the road; 2) the expanding base of electric vehicles result in a bigger, more easily addressable market than ICE (internal combustion engines) vehicles; and 3) autonomous vehicles would require AI – in fact they will require edge computing, since we cannot risk them losing connection to some remote server while driving on the road.

We believe the auto market for GPUs will only truly become substantial when autonomous driving technologies become more mature.

While Nvidia has successfully sold its Orin system-on-chip to BYD, Hyundai and Polestar, we believe the size for this market will only truly take off when autonomous driving software is more mature.

This is because of the two main use cases envisioned for vehicular chips. One is for self-driving itself, and the other is for in-vehicle gaming, which Nvidia targets with its GeForce Now cloud gaming service. Both would be much more feasible if the driver did not have to be pre-occupied with driving.

In-vehicle gaming will likely only form a small addition to the gaming segment.

While there are specific instances, such as back-seat gaming for families with children that may work well, the challenges for Nvidia are threefold.

One, the driver and their spouse sitting in the front are usually the key decision-makers in making purchases, and not the children who might be gaming in the back.

Two, EVs are again the most directly addressable market for gaming, but the largest EV market for now is China, where again local substitutes may win over, especially if there are further export controls from the US side, or indeed data concerns from the China side. As we saw, the latter led to the delisting of Didi from the US.

Three, the current business model for GeForce Now is that you can stream games you already own on the PC. This will likely see limited traction in the world’s largest two gaming (and automobile) markets, the US and China, which constitute over half the global market. Even by 2034, researchers expect that most vehicles sold in the US will still be ICE-based. Meanwhile in China, which has the largest EV market, the preference is for mobile gaming and in-game purchase-driven models.

Indeed, due to the popularity of PC gaming and the EU’s 2035 zero-emissions target for new cars sold, Europe may well become the largest addressable market for GeForce Now.

The automotive SoC industry may grow to be $100-150 Bn by 2034, but there is no guarantee that Nvidia will emerge dominant.

Taking a step back, various studies are forecasting a $100-150 Bn automotive SoC industry by 2034, or on average, around $1,000 per vehicle, which seems rather high but not outside the realms of plausibility (high-end SoCs for mobile phones typically cost under $200).

For reference, Goldman Sachs forecasted ~60 million EVs to be sold in 2035, comprising half of all vehicles, while GlobalData anticipates ~50 million EVs to be sold in 2035.

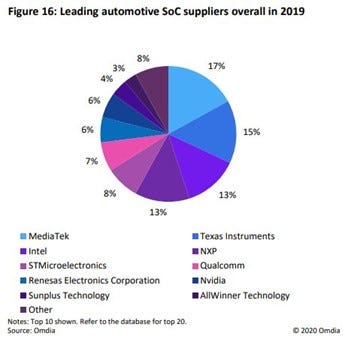

Source: Omdia

The automotive SoC sector is highly fragmented, with MediaTek, Texas Instruments, Intel, NXP, STMicroelectronics, Qualcomm, Renesas Electronics and Nvidia all in the mix, according to Omdia in the above image (the statistics are somewhat dated but we believe to still be relevant).

There is no guarantee that Nvidia will emerge victorious in this segment.

Moreover, OEMs may increasingly see SoC design as a core competency. Tesla designs its own SoCs, which we believe to be a highly strategic decision – otherwise the auto brands may become little more than the new IBMs to Nvidia’s Intel.

Finally, mobile phone brands such as Xiaomi and Huawei are plunging into the EV market, in search of further growth. Oppo and Vivo, too, may make their moves soon. These companies will have existing partnerships with the mobile SoC designers, a further obstacle to Nvidia’s ambitions in the sector.

Given all these concerns, we believe that Nvidia may take a leading position if L4 driving becomes reality before 2034 – due to the increased computing power this will demand, and the advantages afforded by its CUDA stack under such circumstances. Otherwise, mobile SoCs – and potentially Chinese challengers – will likely end up holding significant market share.

So, we will assign equal probability to three scenarios:

1/3 probability of Bull case. Nvidia becomes a leader in the space, gaining 60% market share (comparable to its lead over AMD in the computer graphics space), or $90 Bn of a $150 Bn market.

1/3 probability of Base case. Nvidia is one of the top contenders, maintaining roughly 10% market share or $12 Bn of a $120 Bn market.

1/3 probability of Bear case. Nvidia drops out of the sector like Tegra on mobile, hence accounting for $0 Bn.

The weighted average of the above scenarios comes out to be $34 Bn.

Wrapping up

Overall, for 2034, we have estimated the following:

Gaming. $30-35 Bn in 2034 from gaming as the base case, $50-100 Bn in an off chance.

Cryptocurrencies. Less than $5 Bn annualized.

AI & high-performance / general-purpose computing. ~$100 Bn as a very ballpark figure, though Nvidia will be unlikely to capture it all.

Auto. $34 Bn as a weighted average, $150 Bn in bullish upside scenario.

Summing over all these possibilities, we get:

Which is higher than our initial $333 Bn “target”. However, this would require Nvidia hitting the ball out of the park for all three major segments (Gaming, AI & Auto).

This is highly unlikely, given that for any individual bullish case, we would assign under 50% probability of occurrence. Furthermore, it would ignore any discounting necessary for such distant projections to the present day.

Instead, in the more likely base case, we would expect around:

This would mark a discount of 50% or more versus the current share price.

Limitations of the analysis

Apart from the very rough and approximate nature of the above analysis, the main limitations would be if Nvidia found new sources of growth, or improved its net margins further due to e.g., increased pricing power or enjoy more software-based revenue rather than have it tied to hardware.

Of course, none of the above precludes the share price going up further with additional multiple expansion due to the prevailing market sentiment, so we would not consider shorting the stock. However, this is why Nvidia is not currently on our buy list.

Disclaimer: This should not be construed as investment advice. Please do your own research or consult an independent financial advisor. Alpha Exponent is not a licensed investment advisor; any assertions in these articles are the opinions of the contributors

Edit: updated a typo, formatting and corrected spelling of Grok to Groq in one instance. After releasing the note, we since have initiated a short position in NVDA as a hedge against another of our holdings.