The mythical multibagger, that rarest of beasts, has drawn much attention, including multiple books such as “100 to 1 in the stock market” by Phelps, and “100 baggers” by Mayer. We start this series, though, with a look at “the Makings of a Multibagger”, a fine study conducted by the 2020 class of summer interns at Alta Fox Capital.

It is very instructive, though does come with some limitations, which we point out first. The interpretation of such studies can be easily prone to survivorship bias (indeed, some degree of bias in time period for this study is perhaps difficult to avoid), which we also highlight where relevant.

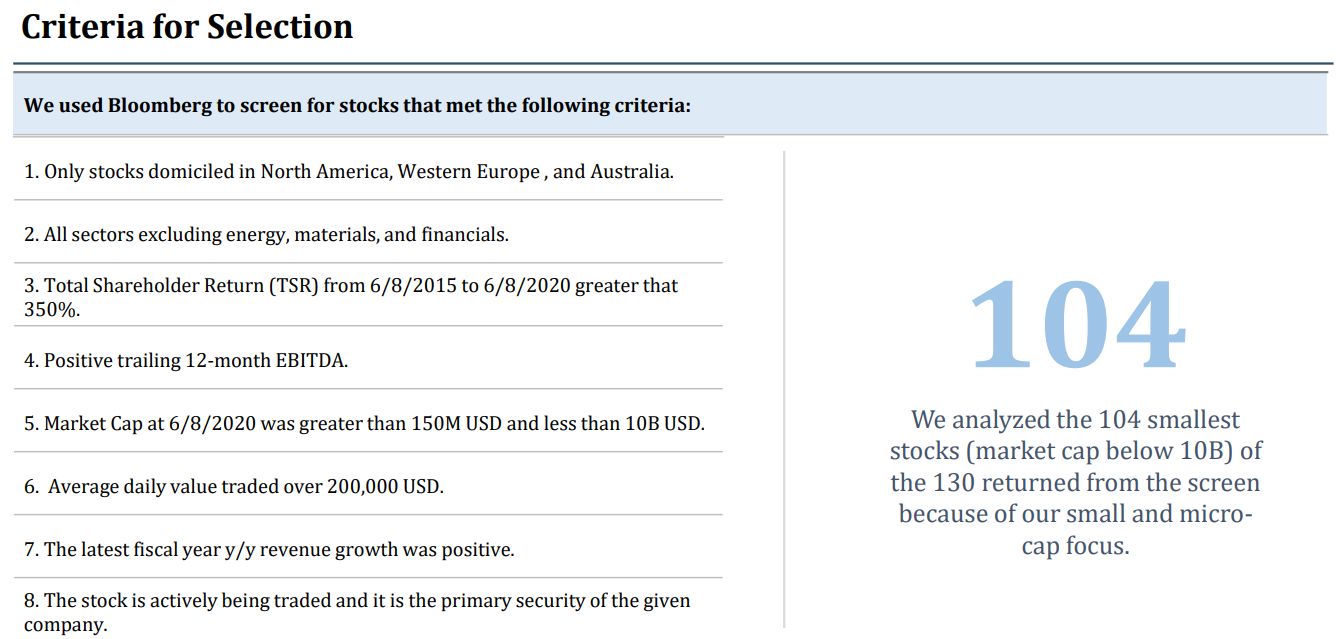

The study encapsulated 104 companies, with 2015-2020 total shareholder returns ranging from 350% to over 9,000%.

The study placed an upper bound for the June 2020 market cap at US$10 Bn.

This restriction, combined with the ambitious 350% five-year return requirement (translating into over 35% CAGR), means that even the largest companies in the universe would have a market cap around US$2.2 Bn, or a borderline midcap.

It also excludes more speculative picks that have negative trailing 12-month EBITDA, or which have negative YoY revenue growth, and has market cap and volume restrictions (though these appear to have been applied to the 2020 data, rather than retrospectively applied to the 2015 data).

Also excluded are the Asian markets, and sectors like energy, materials and financials, so the same criteria may not apply to those.

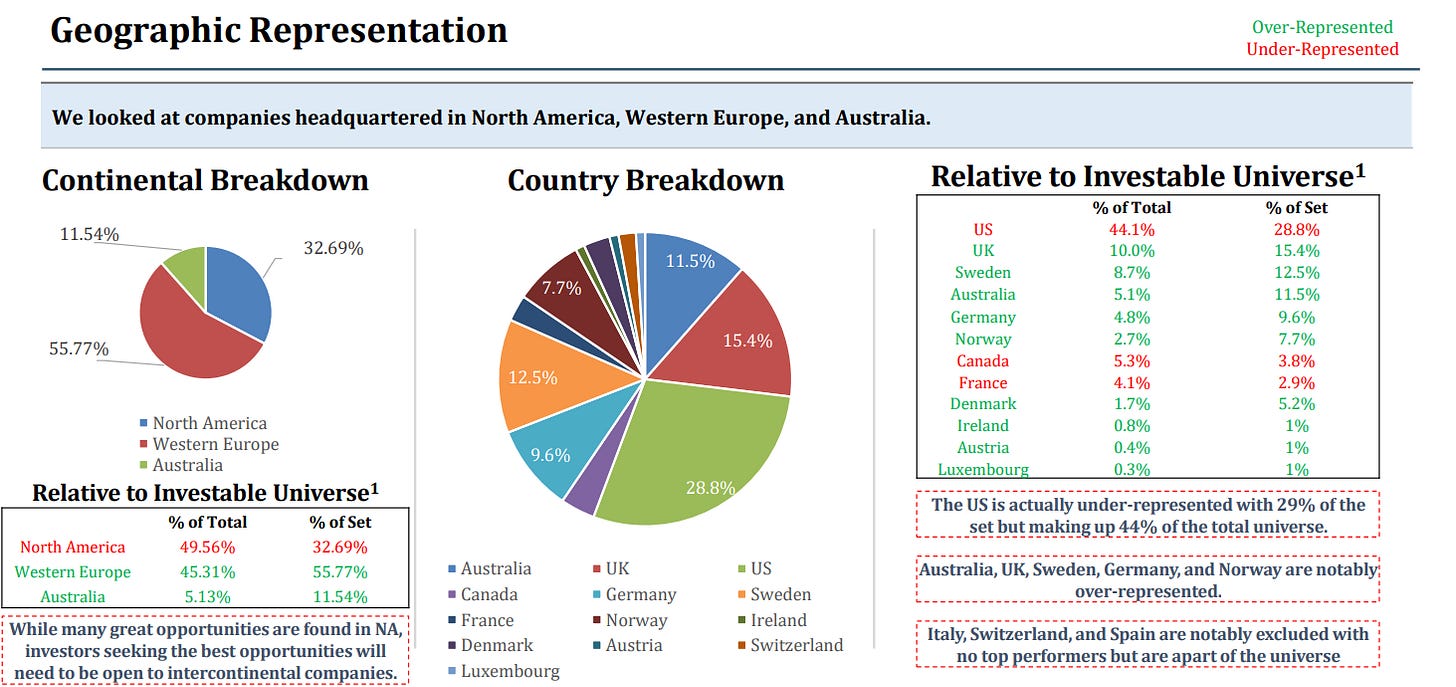

As the biggest component of global equity, the US market held the greatest share of multibaggers, yet was actually under-represented overall. Instead, the UK, Sweden, Australia, and Germany were found to have been over-represented.

Given that the GBP and the SEK each weakened some 20%, and the AUD high single-digits against the USD, forex fluctuations also likely overstated these returns in pure dollar terms.

Note that the second, third and fourth largest stock markets globally (China, Japan and India) have been excluded. While it would be difficult to investing in single Indian stocks (apart from ADRs and GDRs) unless you are a nonresident Indian, both China and Japan are open to foreign investors.

The SEA markets may also be potential hunting grounds for multibaggers in the future.

Technology and healthcare were especially overrepresented in the sample, though consumer discretionary also put in a solid showing.

The tech sector, especially software firms, tend to have high margins and high scalability. Emerging tech trends also tend to be newer and more difficult to assess for many seasoned investors - an out-of-sample challenge.

Similarly, healthcare, in particular medical device companies, punched above their weight as well. While consumer discretionary companies were under-represented versus the investable universe, they still formed more than one-fifth of the multibagger set.

Not coincidentally, these are the more “trendy” sectors more prone to disruption, and also rich hunting grounds for VCs - though more for non-listed companies - especially in the US, where the capital markets are more developed.

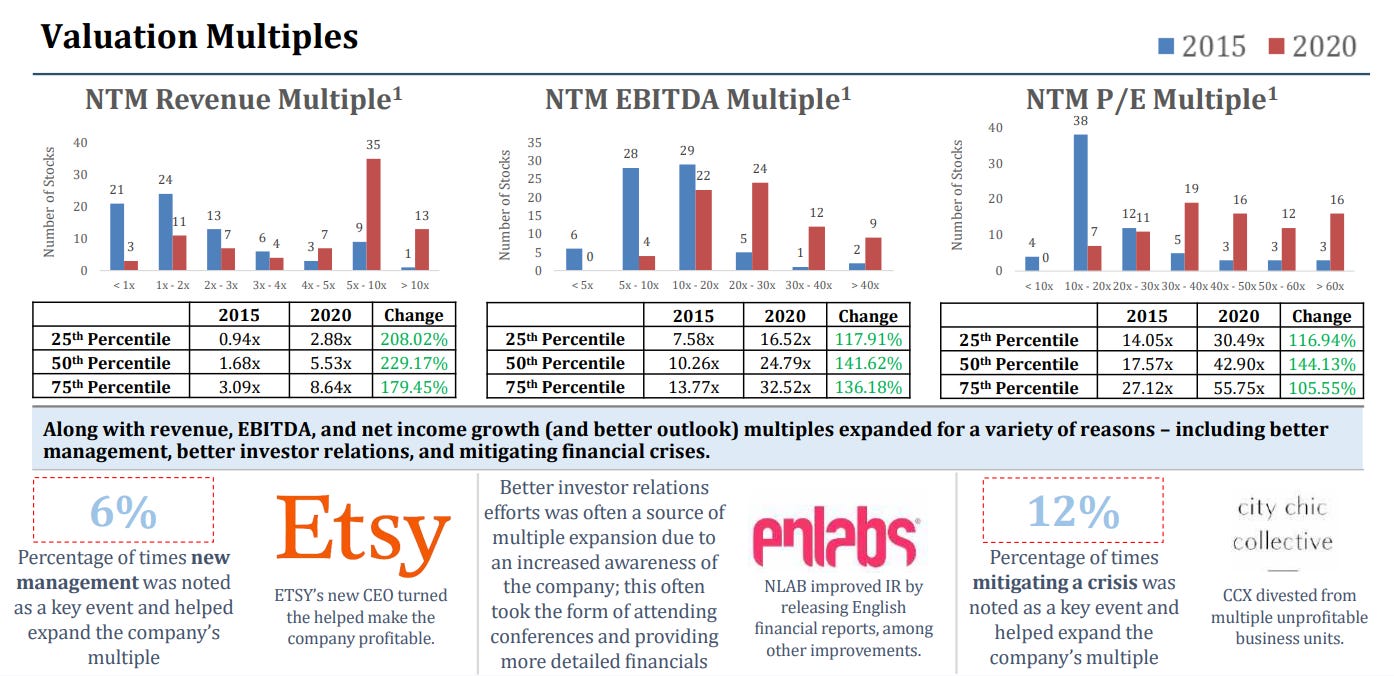

Interestingly, returns were roughly equally driven by EBITDA growth and multiple expansion, with dividends playing a minimal role.

This is unsurprising, given that such multibaggers would have to be almost growth companies by definition, and it would not make sense for them to redistribute a lot of capital back to shareholders in the form of dividends or buybacks.

Indeed, more than 80% of companies were found to have more shares outstanding in 2020 than 2015 in the study.

Instead, most of those companies chose to spend capital on acquisitions, tapping into inorganic as well as organic growth.

Note that the figures in the slide above and below were based on the subjective judgements of the authors of the study.

Apart from the subjectivity, another limitation is that we do not know the prior distribution of the companies’ barriers to entry. That is, if 50% of the universe had high barriers to entry, then the 42% given above would actually mean an under-representation.

Overall however, it would intuitively make sense that at least a moderate level of competitive advantages and moats would be needed against competitors.

We would suggest a slightly different set of screening criteria:

Country. In addition to the UK, Sweden, Germany, Norway and Australia, we would also consider including the US (Asian markets may also be interesting but would require further study).

Industry. Apart from technology and healthcare, we would think about adding back in consumer discretionary, which accounted for over a fifth of the multibaggers.

Size. There is some ambiguity how the market cap upper bound was applied to the original sample. At the risk of diluting any predictive powers of the other criteria here, we would loosen this to a US$5 Bn upper bound instead, and separately study the dynamics of large cap multibaggers.

Multiples. As the authors remarked, a key limitation of the study is that a lot of the companies in 2015 did not have next-twelve-month multiples. If we want to apply these multiples criteria, we would need to produce forecasts for all the companies in the investable universe.

Poll time

Notably, the distribution of NTM revenue multiples appears to have a very long tail, so using the suggested criterion would already filter out 40% of the final set.

Due to the specific criteria imposed, the top three firms by TSR were all nanocaps in 2015, with market caps of under US$10 Mn.

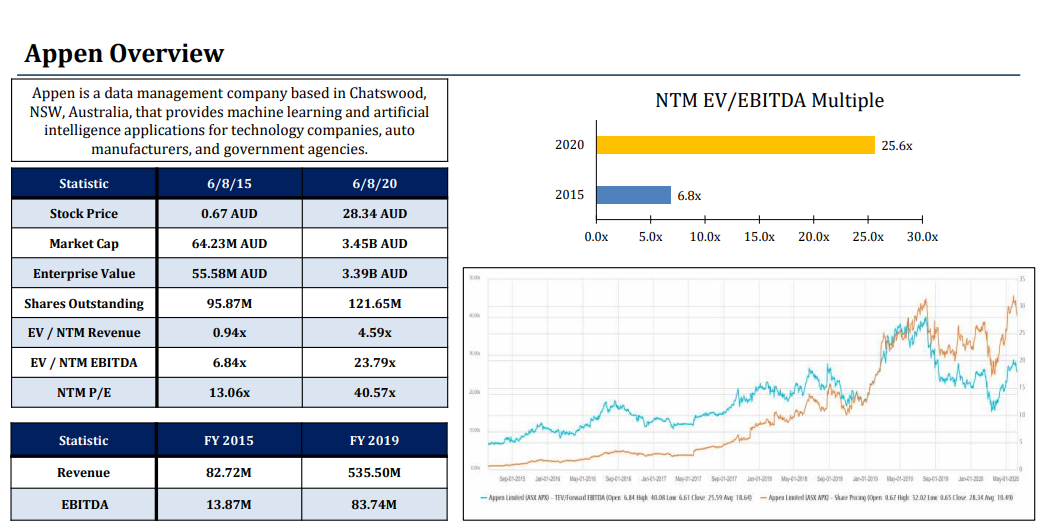

Number four, Appen, was the first decently-sized company with a market cap of AU$ 64Mn in 2015, on the borderline between microcap and smallcap. It went on to return over 4,600% by 2020.

Our key conclusions and perspectives are as follows.

Do:

Go international. Partially because of the mature VC scene in the US, startups are getting rich valuations before they list, reducing the growth after listing. Markets less covered by VCs, or indeed, companies with characteristics not favored by VCs may instead turn out to be hidden multibaggers.

Expect additional share issuance. Share-based compensation may be a factor, while the companies may also seek to raise additional funding from public investors - which is preferable to them being taken private.

Seek niches. Hidden diamonds in the rough - neglected yet strong companies not covered by analysts may be fertile grounds for future multibaggers.

Don’t:

Forget the US. It is still the largest single market for multibaggers, and with the heightened interest rates post-pandemic, some listings may be coming that have not been so VC-inflated.

Penalize M&A. Both organic and inorganic growth are successfully pursued by multibaggers. Completing an accretive acquisition would create an important lever for growth, and is a mark of good capital allocation.

Expect dividends or buybacks. Management would be too busy using that capital for M&A, R&D or making sales, which would create greater value for shareholders.

Full disclosure: This is not a solicitation to buy or sell. We have no current business relationships with the companies mentioned in this note, and are not paid to write this piece (other than paying fellow exponents of the research).

Disclaimer: This should not be construed as investment advice. Please do your own research or consult an independent financial advisor. Alpha Exponent is not a licensed investment advisor; any assertions in these articles are the opinions of the contributors.

Edit: corrected two typos from an earlier version. An earlier version incorrectly assumed the 350% meant returning 250% or CAGR of 28%; this has now been clarified, and indeed returning 350% equates to CAGR of 35%.

Very interesting and insightful, Thank you. Would be cautious however about extrapolating this into the future considering there was no cost of capital and hardcore liquidity

Amazing study, thank you for sharing!