In the first installment of this series, Duan just announced his resignation from Subor.

According to the agreement with Yihua, the parent company, Duan was entitled to 20% of Subor’s profits, though he shared it with the team instead of keeping it all.

The issue was that Yihua often diverted Subor’s profits to subsidize lossmaking businesses. This led to tensions, with Subor urgently needing cash to invest in growth. Yet Yihua and Subor were entangled, sharing assets, liabilities and even employees.

Duan previously proposed reforms to move Yihua closer to a joint-stock company.

We shall see why this was so important to him later — notably Duan made extensive use of equity to align incentives, and could spot where misalignments might lie in his investments

This meant being able to reward employees with equity and ownership, a resolution of the muddied accounting, and if Yihua ever needed cash for another business unit, it could sell stock and not have to lean on Subor.

Of course, this stalled within Yihua, even after he pressed repeatedly.

Why free the golden goose?

Nor could Duan’s sponsor, Chen, the Yihua GM who assigned him to Subor, push through Duan’s proposals. Duan declined the offer of increased pay, noting it did not fix the root problem.

Chen realized there was only one thing left to do.

‘… when I left, I had an arrangement with the boss [Chen]. He asked if I wanted to start another company, and I said yes. He then asked if I wanted to take some people away, and I said yes, if that’s OK. He asked how many I wanted to take, and I said 10 would be enough, and your company should keep operating as normal. He said, can you just take 6? I said OK, then 6 it is. So we really only took 6 people’

— Duan Yongping

Duan and Chen had a further gentleman’s agreement that Duan will not compete with Subor in the domestic Chinese market, in the same line of business.

Then Chen gifted Duan with a Mercedes-Benz, and threw him a big going-away party.

Duan began thinking about moving to the US, where his girlfriend was, but his coworkers from Subor wanted to prove that they could start up from scratch.

After they left, Subor underwent drastic changes and numerous Duan-era managers were replaced. Many jumped ship and flocked to Duan, first a trickle, then a flood.

Duan initially owned 70% of the startup, but to give incentivize everyone, he gradually diluted his stake. When others did not have the cash, he lent them the money.

‘It’s OK, each buck I lend you, you can buy a buck’s worth of shares. In the future, you can repay with the profits from [sales of] shares or the dividends’

— Duan Yongping

Compared to directly awarding equity, this helped to foster a psychological sense of ownership and responsibility.

‘Show me the incentive, and I’ll show you the outcome’

— Charlie Munger

After the first month, dozens more came, and after the first year, Duan’s team was hundreds strong.

‘If they really wanted to come, I couldn’t refuse to take them in. I felt I had a responsibility’

— Duan Yongping

Yet because of his promise not to compete in China, he directed his startup, initially named Ligao and then renamed to BBK, to serve Russia.

The country was not altogether new to him: as Duan prepared to leave Subor, it had indirectly entered the Russian market by becoming the OEM for Dendy consoles.

But there was little for Duan, who worked mostly in marketing and did not know Russian, to actually do. Consequently, he spent much of that year on the golf course.

BBK failed, perhaps unsurprisingly.

Stubborn to a fault, Duan retained a Chinese company name, despite the prevalence of Chinese companies registering in Japan and using Japanese names. He also stuck to the ‘Made in China’ label, refusing to misrepresent the origin like some others.

Because Chinese goods were associated with shoddy quality in Russia, consumers were not receptive. So they ended up losing money.

Worse still, they experienced cashflow issues due to the lengthy forex conversion process to take ruble payments into China.

By 1997, BBK only had CN ¥20k ($2.4k) in cash left.

The situation was exacerbated by their entry to the domestic Chinese market.

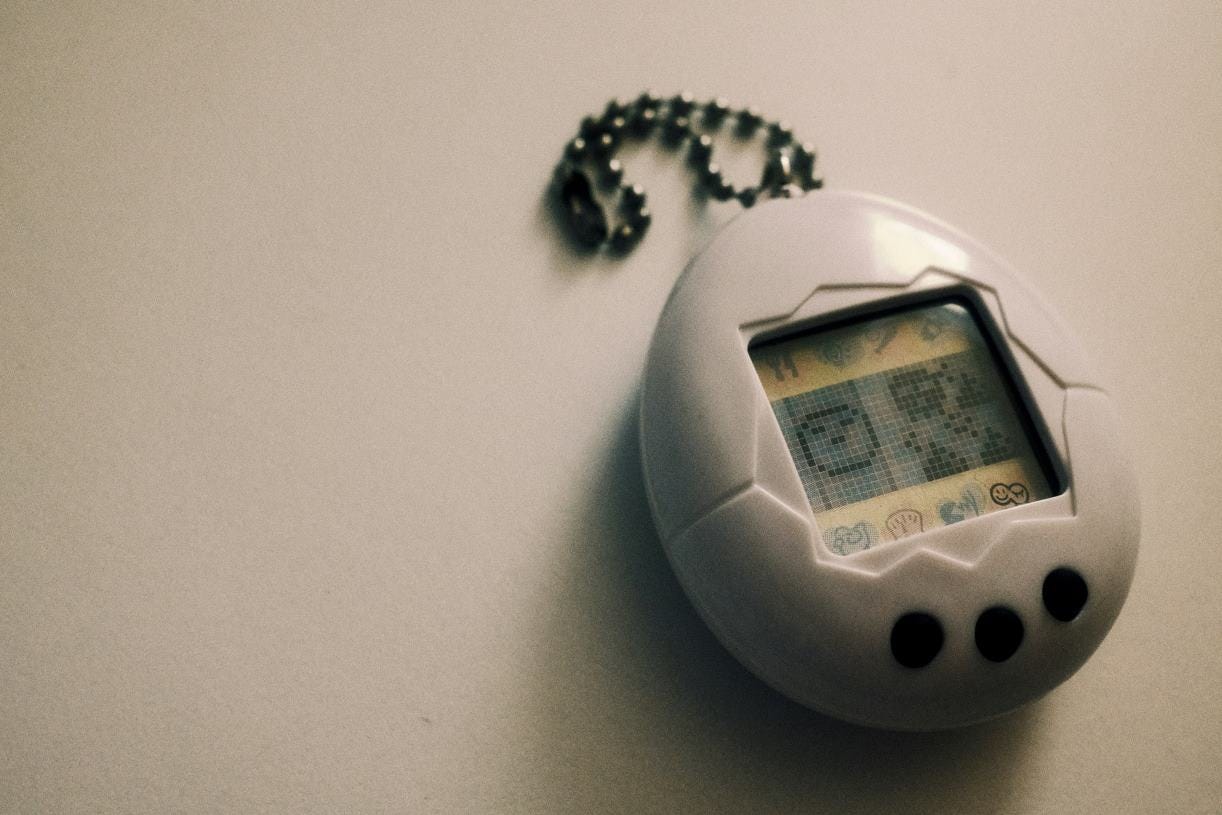

Bandai, the innovative Japanese toymakers, kickstarted the digital pet phenomenon that swept across the world, initially targeting girls with Tamagotchi and then boys with Digimon. The trend culminated with Nintendo’s Pokémon.

The US-based Tiger Electronics emulated Bandai and found success with Giga Pets. In China, again a wave of manufacturers piled into digital pet production. Duan was not to be left behind, and BBK’s digital pets quickly found traction.

However, large numbers of digital pets were disappearing from the production lines. All over the world, other manufacturers body-searched assembly line workers each shift, and BBK supervisors proposed to do the same.

Although it may be taken to be a sign of distrust and disrespect against employees, there appeared to be no alternative. After some deliberation, Duan made up his mind.

‘Let’s stop producing them’

— Duan Yongping

This cost BBK CN ¥16 million ($2 million).

Nonetheless, another opportunity came. A few years earlier, a Chinese businessman called Jiang met a Chinese American, Sun, who created the prototype for one of the world’s earliest VCD players. Together they formed a new company Wyan.

Though Japanese and European engineers from JVC, Sony, Matsushita and Philips created the VCD format, Wyan won the race to commercialization, lowering costs and maintaining quality to enable mass adoption with prices under CN¥ 5,000 ($600).

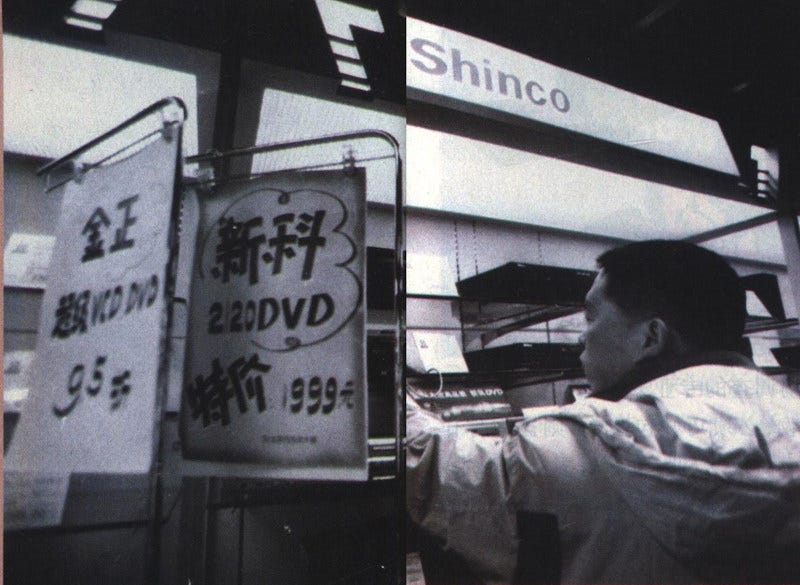

VCD players became extremely popular in developing markets, where VHS (Video Home System) penetration was low. The number of VCD player manufacturers soon ballooned from a handful to hundreds, and Wyan fell behind.

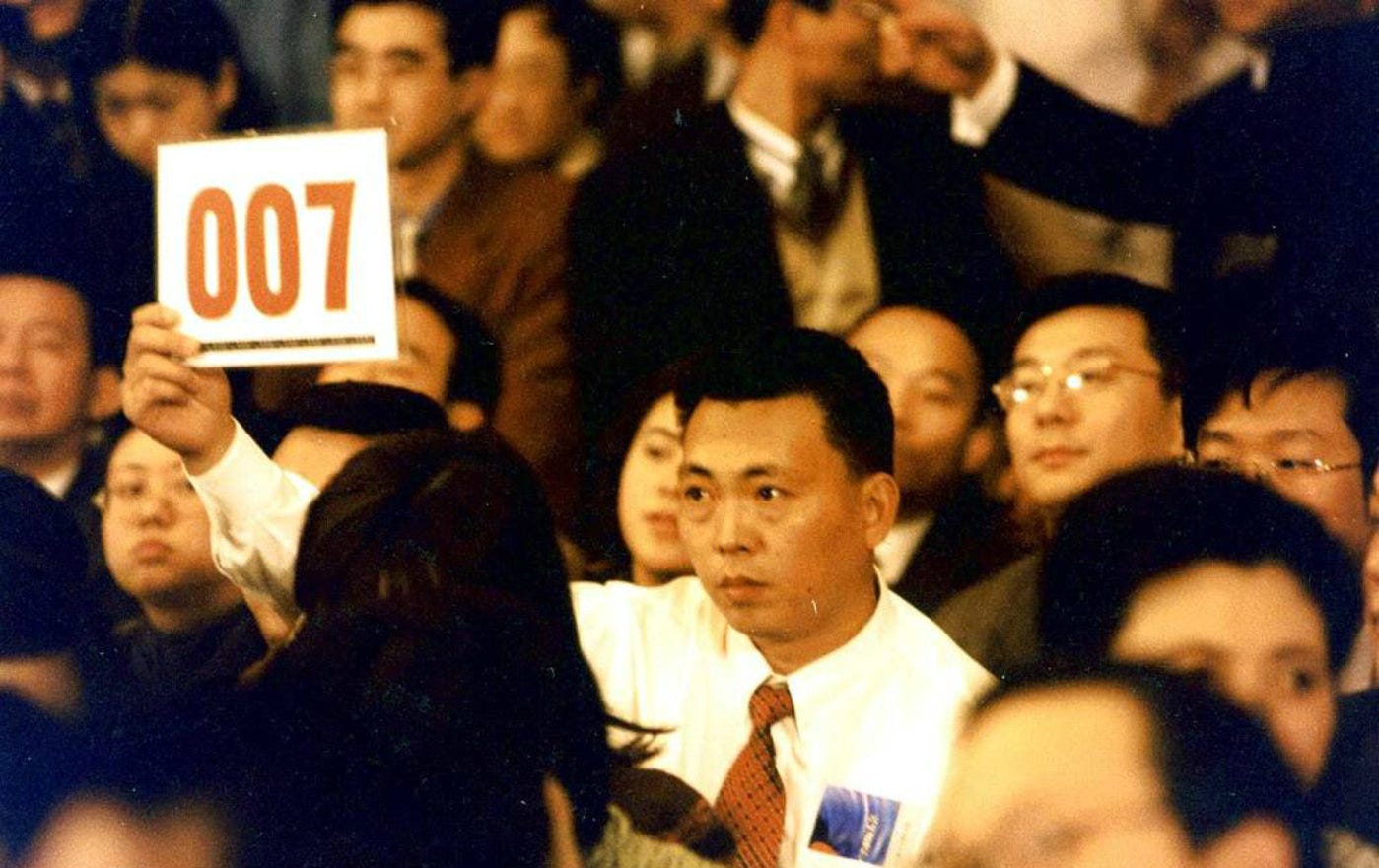

The then fledging market, however, gained the attention of Duan, who again decided to tap into the advertising firepower of CCTV.

Marketing came easily to Duan, who recognized the primacy and recency effects, and targeted the first and last slots during commercial breaks. When others caught on, he shifted his focus to whatever would have the highest ROI.

In late 1996, he procured a CCTV commercial slot for ¥80 million ($10 million), enough to pay 10k employees above average wages for a year in China at the time.

Ruble forex conversion issues, the curtailed foray into digital pets and the outsize marketing bet together caused a cash crunch for BBK.

At this critical juncture, Duan rallied together his suppliers, and told them about BBK’s cashflow difficulties.

He asked for an extension of credit at 1% interest per month, with the optionality of converting the cash repayments into BBK’s equity. Some suppliers knew Duan from his Subor days, and many took up the offer to get a stake in BBK.

Somehow, Duan turned the crisis into what was to become a lasting moat for BBK.

‘When written in Chinese, the word “crisis” is composed of two characters. One represents danger and the other represents opportunity’

— John F. Kennedy

Nor did he stop with the suppliers. He offered distributors the chance to become BBK shareholders as well.

Many distributors did business with Duan from Subor through to BBK. A lot of them picked up shares, and some eventually joined BBK itself.

To provide equity incentives, Duan’s stake gradually decreased to under 20%.

But the financial pressure remained, as fierce competition in China resulted in drastic price cuts. The going price of a VCD player fell by nearly 50% in 1996 alone.

BBK’s financial position strengthened after Acer acquired 19% to become the biggest shareholders. It turned out Acer had struggled to make headway in VCD players, tried to partner with Subor, but learned about Duan’s leaving to found BBK.

BBK made steady progress as Duan repeated his signature focus on build quality and aftersales service, setting up hundreds of servicing centers throughout China.

At this time, all eyes were on IDALL, which was led by a charismatic CEO, Hu. In his mid-twenties, Hu was a former farmer and a prodigious sales and marketing talent.

Duan and Hu knew each other personally; both men looked up to the Japanese electronics giant, Panasonic, and wanted to build the Chinese equivalent.

Hu was from Zhongshan, where Subor was based, and had previously entered the ‘learning machine’ market created by Duan, but later exited with losses. He next ventured into the VCD player market.

Fatefully, Duan followed him.

Hu had little initial funding, but somehow convinced distributors to pay upfront, an almost unheard of practice in a market where generous credit terms were the norm.

Hu’s IDALL then paid CN ¥82 million ($10 million) for a CCTV commercial slot in 1996, one-upping Duan’s BBK, which paid CN ¥80 million for another slot.

To obtain funding, Hu went one step further, only supplying distributors who prepaid. This was only possible because IDALL was in high demand.

Hu imitated Duan’s earlier exploits at Subor, plowing in the entire year’s profits to hire Jackie Chan and advertise on CCTV, using the slogan ‘IDALL VCD, good Kungfu’.

The year after, IDALL doubled down, bidding a record-breaking CN ¥210 million ($25 million) for the top ad slot, beating out BBK’s CN ¥182 million.

Hu taking Jackie Chan naturally made him unavailable to Duan. In response, Duan signed up the rising martial arts star, Jet Li, with the slogan ‘BBK VCD, true Kungfu’. The ensuing ad battle became the talk of town.

IDALL’s sales took off, growing 700% year-on-year to reach CN ¥1.6 billion ($190 million) in 1997, around half of the number one, Shinco.

That year, Hu was 28.

IDALL was 2.

‘When I read the Sun Tzu, the line that left the deepest impression was “First make yourself unbeatable, and wait for when the enemy can be beaten. As you can prevent the enemy’s victory, so can the enemy determine your victory. Thus those skilled in war can make themselves invulnerable, but cannot force enemies to become vulnerable’

— Duan Yongping

To win share, IDALL brought down price relentlessly, going from nearly CN ¥3,000 at the end of 1995 to under CN ¥2,000 in mid-1996, and cutting prices again in 1997.

Unlike rivals who followed IDALL into the fray, Duan tightened controls so managers required his approval to reduce prices, aiming to avoid accidental price wars.

By 1998, IDALL VCD players sold a little too well, and kept running out of stock. Hu began raising prices back up by ¥CN 250 ($80). But other players did not follow suit.

Hu had misread the market, and a supply glut quickly formed. To make up for the lost income, he then launched an initiative to boost service revenues.

In addition to cutting prices back down, IDALL gave away free content on a regular basis, and offered discounted software to customers via retail outlets.

But they underestimated the capital required and difficulty of operating retailers, which they had little experience in. Soon they had to halt the project.

Instead, Hu went after the market leader, Shinco, which dominated the eastern China market, setting up shop in the same department stores. By offering lots of free gifts to customers, IDALL was able to tie Shinco’s market share.

This came at grievous cost, since Shinco had a healthier balance sheet. Importantly, IDALL also left the southern China market, its original stronghold, wide open.

Duan’s BBK and other competitors took this opportunity to cut prices and gained significant share from both IDALL and Shinco.

Seeking growth elsewhere, Hu took IDALL into telephones, digital televisions and speakers, further losing focus and profitability.

IDALL’s downfall was sudden and swift.

Infighting between Hu and other shareholders triggered a lawsuit, which then spiraled into a liquidity crisis as suppliers demanded repayment. More lawsuits ensued, finally landing Hu in jail for misappropriation of funds.

Notably, even into the crisis, IDALL had good standing among customers: product and service quality were fine.

Not long after, BBK also entered the telephone market, but with much more success.

After a lengthy struggle, they unseated the top dog, TCL (originally Telephone Communication Limited), which was crowned the ‘King of Chinese telephones’ by the Chinese State Council only a few years prior.

They also did well with other products such as voice recorders and of course, ‘learning machines’ (AKA gaming consoles). But that is another story for another time.

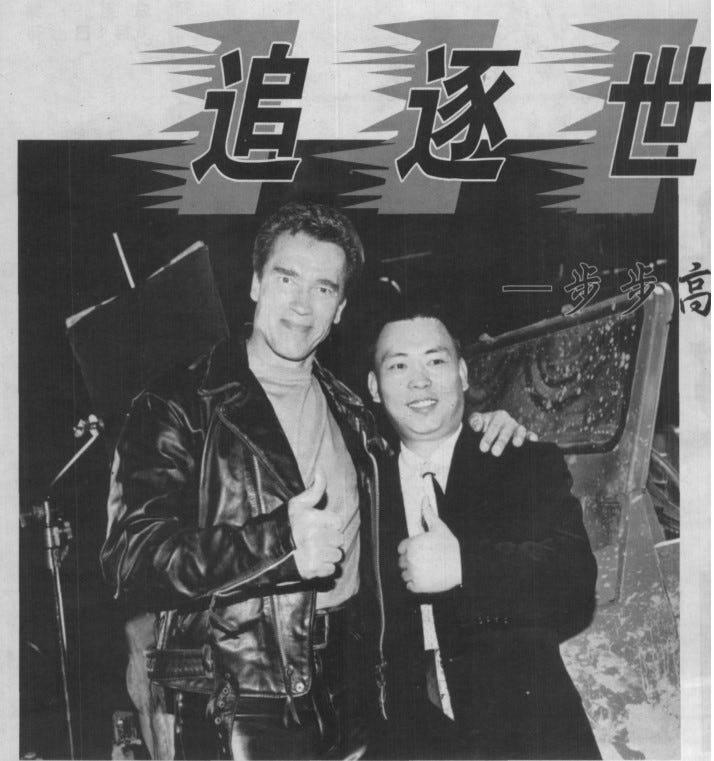

BBK hired stars such as Stephen Chow and A-Mei for adverts, in addition to Jet Li. When the VCD to DVD shift began, Duan looked to hire Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The future Governator signed up for $2.5 million over two years, with payment half upfront, and half upon completion.

Unfortunately, CCTV broadcast the commercials for only two months before complaints put a stop to them.

‘They didn’t let you use foreigners in advertising… If you didn’t have a primetime slot it might’ve been OK, since there would’ve been fewer viewers and fewer complaints… Why was it like that? I don’t really understand, but it may have been a bit of what I’d call narrow-minded racism…’

— Duan Yongping

BBK negotiated for a reduced final payment. A 40% reduction was the agreed-upon compromise.

Even as they expected him to sign off on the updated agreement, Duan instead told Schwarzenegger’s incredulous lawyer that BBK would pay in full.

‘I always felt they felt we were trying to cheat them, that they did not really understand the situation… so I said to our people, this doesn’t seem to fit with our values… it’s not his fault right?’

— Duan Yongping

Duan’s reasoning was that Schwarzenegger delivered his end of the agreement, and it was more proper for BBK to pick up the tab for situations outside everyone’s control.

BBK grew swiftly nonetheless, but as it found its footing, Duan had bigger fish to fry.

In 1998, his girlfriend Liu returned to visit China and they got married. They agreed to settle down in the US where she worked as a journalist.

The following year saw the birth of Duan’s son. He began to take his foot off the pedal, prioritizing family time and declining any calls on weekends.

He also started to step back from frontlines, reorganizing BBK into three separate companies, one for educational electronics, one for telecom devices, and one for audiovisual entertainment.

Each had entirely separate management teams and their own P&L, and Duan was chairperson of the BBK Group, which held shares in them all.

In 2000, Duan began applying for a US green card. Despite his preparations, his green card was approved much faster than he anticipated, and he had to hurry the process.

By fortune or design, this coincided with the gaming console ban in China, which banned all the production and sales of consoles, and lasted over fifteen years.

Sector wide bans such as these are not new in China; instead there may be signs ahead of time, and can bring unexpected opportunities elsewhere

The year after, Duan was in the US with a lot of time on his hands and little to do apart from playing video games and golfing. His favorite golf player was Tiger Woods, whom he hired to improve his own game.

Investing became another hobby.

He did not find books about technical investing to his liking. By chance, he came across a book about Warren Buffett, and what Buffett had to say made sense.

‘In fact, before reading about Buffett, those concepts were already in my mind, but once I saw that Buffett was thinking about [investing] like this, and used this to become the world’s second richest man, I found confidence’

— Duan Yongping

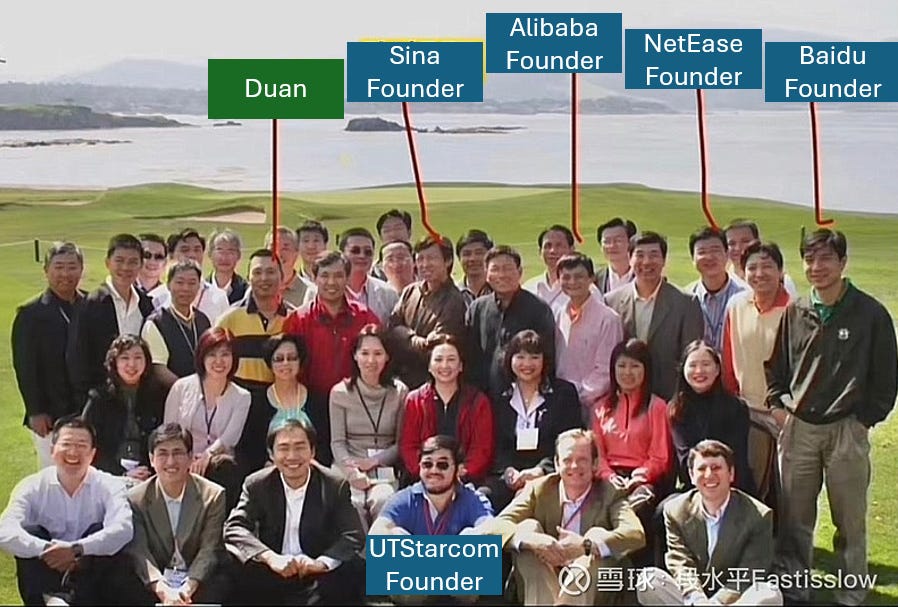

Duan rather enjoyed playing games from NetEase, a Chinese gaming company founded during the dotcom era.

NetEase floated four months after the dotcom burst. It opened at $15.5, just below the bottom of its range, rose slightly, and went downwards from there.

A year later, accounting irregularities rocked the company. Revenues had to be restated downwards, and both the CEO and COO stepped down. Bearish sentiment compounded. Ding, the founder of NetEase, returned to lead the company.

At its nadir, the stock price fell below $0.5, a hefty 97% drawdown from the IPO price.

At one stage, trading in the shares was suspended.

Though skeptical about dotcoms, Duan sensed opportunity. Because of his experience with gaming consoles, he knew how large the Chinese gaming market was.

‘Invest in what you know’

— Peter Lynch

Even years earlier, console volumes sold had overtaken Japan, and were only second to the US. So Duan set BBK’s investment team a task: to play lots and lots of video games.

They gained a good sense of the Chinese video games market, the relative quality of the games, and how the companies moved with respect to market demand. All this was fed back to Duan.

He started buying NetEase in late 2001.

Duan also noticed Apple’s potential, but hesitated since he felt he did not understand the business well enough.

Ding graduated from the same alma mater as Duan, though nearly a decade later. He heard that Duan knew a thing or two about marketing, and came to seek his expertise.

Duan readily agreed and heard him out. He agreed that Ding’s plan of developing online games was the right path, giving Ding renewed confidence in his strategy.

The console gaming ban provided an improbable impetus to the growth of the online PC gaming market, and Ding was readying his game, Westward Journey Online.

At that time, NetEase was not yet profitable, but each share of NetEase was entitled to $2 in cash, and Duan felt Ding was trustworthy. Outstanding lawsuits were the only concern, and that Duan had people look them over. They figured it was manageable.

Duan had one million dollars in spare cash and put it all into NetEase. Then he borrowed another and bought 1.52 million shares of NetEase, giving him an initial entry price of around $0.8 for each share.

Later he bought even more and became one of the biggest shareholders, owning 6.8% of the outstanding shares.

Upon launch in late 2001, Westward Journey Online tanked, plagued by technical issues. Ding sent it back for rework.

Around this time, constantly hunting for new technical talent, Ding found the top-ranked computer science student at Zhejiang University, whom he introduced later introduced to Duan.

The reworked game, Westward Journey Online II, turned the fortune of NetEase around after launch. Based on the centuries-old IP of Journey to the West, it hit over 0.5 million peak concurrent users in 2005, exceeding 50 million registered users.

By late 2003, NetEase’s share price broke $70.

Ding was ranked the wealthiest man in China by Forbes in 2003, with $1 billion to his name - the country’s first Internet billionaire. Duan was number 71, with a fortune of CN ¥1 billion, or $120 million, over $100 million of which was from NetEase.

Two years later, NetEase was to break through $100, and the price redoubled in 2009. Duan held through the drawdowns and made - in his words - ‘$100 to $200 million’.

Ding introduced Duan to Huang Zheng, a master’s student at the University of Wisconsin.

Duan enjoyed multiple other successes, and spurred by his newfound confidence and much increased wealth, decided to try his hand in the food and beverage space.

In 2003, the stock price for the restaurant chain Fresh Choice fell to $1.5, even though it still had cashflows of $0.6 per share.

Such a high cashflow yield proved irresistible, and Duan bought over a million shares to become the biggest shareholder with a 27% stake.

He became one of the seven directors, yet found it was impossible to make any impact, partially due to the language barrier.

‘Some of their initiatives, such as continued expansion, raising the prices of items, I’d so many years of product experience, I knew clearly those were wrong. It was extremely foolish, a rapid suicide. We’d die on the spot, but I had little say, and was completely unable to influence the decisions of the board, especially since some decisions were finalized before I even joined’

— Duan Yongping

Buffett of course had similarly negative experiences with activist investing, and came to the same conclusion decades earlier that it did not fit with his style.

In a matter of months, cashflow turned negative, and the company soon filed for bankruptcy. It was delisted from the NASDAQ and Duan lost over a million dollars.

‘Never think you are smarter than the market’

— Duan Yongping

Unfortunately, this was not Duan’s biggest error. Still skeptical of Chinese Internet companies, Duan decided to short Baidu.

It was the biggest investing mistake he ever made.

Adding to the position even as the share price rose, Duan got caught in a short squeeze, eventually losing $150 million on the bet. He decided to not short again.

The lesson was reinforced by a hapless neighbor who saw an ‘opportunity’ to go short on a Chinese education company. The neighbor believed the firm to be committing accounting fraud, and asked for Duan’s opinion.

‘I sent the colleagues [from BBK investment] to study it, and the conclusion was: “this growth in the current situation isn’t manifestly unreasonable.” So I warned the neighbor, “China’s very big, and these growth numbers aren’t impossible”… the share price [then] was $30-40… a couple of weeks ago I met the neighbor playing golf, and asked him if he was still short, and he said yes, the growth was too unbelievable, there must be accounting fraud… that day the share price was $80’

— Duan Yongping

Duan also made an investment in the financial sector, a well-known firm that was established over a century ago. But its share price refused to budge for months.

Still he held on, until the mania in the US housing market led the firm to lever up, saddling it with significant subprime debt and complex derivatives.

Aware of the risk, Duan sold his stake in 2006. He did pocket a gain, though he was dissatisfied with the performance considering the holding period.

The firm’s name? Lehman Brothers.

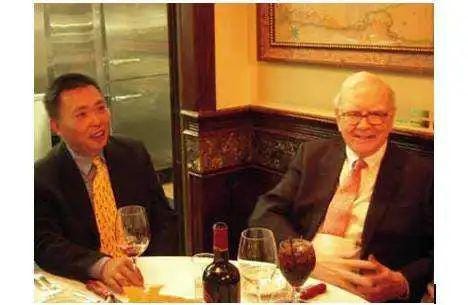

2006 was also the year that Duan had the famous lunch with Buffett, paying $620k for the privilege because he wanted to pay homage to the investing legend.

He also took along Huang, the then student that Ding had taken a shine to, who was by now working for Google. Duan took Huang under his wing and often advised him on important decisions, for example which job offer to take.

‘If Buffett is a super 9-dan (highest rank) in investing, then I am just about 1-dan’

— Duan Yongping

Apart from golf, Duan is a strong amateur go player, peaking at just over 1-dan by his own reckoning. He especially admired the Korean go legend, Lee Chang-ho, who has a ‘thick’, solid style, accumulating subtle advantages to beat opponents.

Lee rarely launched brilliant attacks, but allowed both his and his opponents’ stones to remain in relative harmony. Despite this, he kept winning, often by slimmest of margins, having seen into the ending well in advance.

This is why Lee, nicknamed the ‘Stone Buddha’, is Duan’s favorite go master. In business, investing and life in general, Duan followed a similar philosophy.

Su Shi, the celebrated Scholar-Statesman of the Song Dynasty who rose and fell several times, remaining magnanimous and friendly towards the men who exiled him, described this ‘thick’ style well.

‘Survey widely yet partake wisely, gather thickly yet express sparingly. And that is all my counsel for you’

— Su Shi

The wake of the Great Financial Crisis again brought opportunities. Duan liked the look of General Electric (GE), the storied firm founded by Edison.

Welch was another fêted name associated with GE, and Duan learned a great deal about corporate culture from his book. In 2008, GE’s share price fell throughout the year as earnings fell; its finance division had significant exposure to the credit crunch.

Buffett injected $3 billion for $3 billion in perpetual preferred stock that paid a 10% dividend, and 5-year call warrants to buy $ 3 billion in GE shares at a fixed price.

In true Buffett style, the warrants allowed him the right to buy at $22.25, below the market price of $24.50, immediately giving paper profits of $330 million.

Still the stock price kept dropping - from nearly $40 it halved, and then halved again. It seemed little could obstruct its downward momentum, as it fell below $6.

Insiders began to buy, and Duan initiated a position. He kept adding and invested north of $100 million. In about half a year, the share price more than doubled. Duan made over $100 million and eventually sold his stake to buy Yahoo.

Duan’s exit criteria is flexible - one of them is if there are better opportunities available; another would be if the stock exceeds fair value

This was a play for Alibaba (and thereby Taobao), which was not yet listed, but which Yahoo had a 40% stake in - Jerry Yang was friends with Jack Ma and invested in the company. Incidentally, Duan did not much like the company culture.

However, he broke his own rules to buy Yahoo. While it may seem fuzzy, company culture is the way that a company tends to do things as an organization, and is a critical determinant in efficiency and quality.

Instead of simply holding, Duan sold call options on Yahoo, generating good returns. He later stated that this was an okay but not great investment, and he preferred to hold quality companies for longer term growth.

Under the right circumstances, Duan is even willing to break his own rules for investing, which makes him more difficult to imitate

In January 2011, a large sum of cash became available as Duan’s options had vested.

After an observation period of nearly a decade, Duan finally pulled the trigger on one of his favorite companies, Apple. At this time, Jobs was seriously ill, and many were unsure of Cook. However, Duan had been a fan of Apple for a very long time.

‘Apple’s single-product focus is the pinnacle of the industry, I’ve only ever seen Nintendo reach this level before’

— Duan Yongping

He was confident of Cook’s ability, and took a large position at what now equates to under $12 (accounting for stock splits). It nearly doubled in the next year, but then took a drawdown of over 50%.

Duan held on.

It then resumed its upward path, but again dipped over 35% starting in 2015.

Duan held on.

Then came another 40% drawdown.

Duan still held on, and urged friends and colleagues at Oppo and Vivo - major competitors of Apple - to buy Apple stock. On social media, he often lauded Apple’s products and achievements.

Ironically, Duan and Cook met multiple times, though Duan reckoned that Cook almost certainly did not know who he was at first, though BBK had already become a significant competitor to Apple in China.

Apple became a 20-bagger and Duan’s single most profitable investment in absolute terms.

Duan has an uncanny ability to spot the winners, also making an investment in what became the most valuable company in China, Moutai, and booking a healthy profit.

This he did in 2013, after the suffered from a PR crisis as some of its most famous products failed US lab tests for excessive DEHP, a plasticizer and toxin.

Moutai’s business was also challenged by the anti-corruption crackdown that affected banquet consumption. To Duan, it was the perfect buying opportunity. Like Apple, Moutai was another stock that Duan refused to sell.

It may be because of his experience with NetEase, much of which he sold after the GFC. Duan came to regret this 100-bagger - had he held, it would have become a 1000-bagger - and it taught him to hold on to quality companies.

Still, he made the same mistake with Netflix. If he held, Duan admitted, it would have made a comparable sum to Apple. Instead he sold it for less than a 3-bagger.

Duan kept in touch with Huang over the years as the latter eventually quit Google to try his hand at starting businesses, becoming a serial entrepreneur.

In 2015, Huang was ready for his latest venture. Duan, Ding, and a few other angel investors put together $8 million. They knew and trusted Huang’s abilities.

Huang did not disappoint.

After a few pivots, Pinduoduo went on to list on the NASDAQ within 3 years of founding, having gained 300 million users and inspiring thousands of entrepreneurs.

This was all the more remarkable since Alibaba and JD.com already dominated the ecommerce market with over 80% share. Their position was thought to be uncrackable.

Duan got his first 1,000-bagger (likely closer to a 2,000-bagger). Huang became briefly the wealthiest man in China, much like Ding - and he stepped back to a chairman role when fairly young (aged 41), much like Duan.

As his wealth grew, Duan spent more time on philanthropy. He set up the Enlight Fund with his wife, Liu Xin, in 2004, and approached donations decisions like a full-time job. Ding liked to outsource the decision-making on donations to Duan.

They mostly donated to various educational institutions and universities in China, especially their alma mater, Zhejiang University.

Duan is still an active investor, sharing his experiences insights on various social media platforms such as Weibo and Snowball Finance to his 1 million followers.

More recently, he bought Tencent shares after the first gaming crackdown in 2018, and increased this position over time.

In late 2021, he started a long position in New Oriental by writing put options. The company was hit hard by the crackdown on private tuition in China, and fell over 90% from its peak. It doubled in a year, and again a year later.

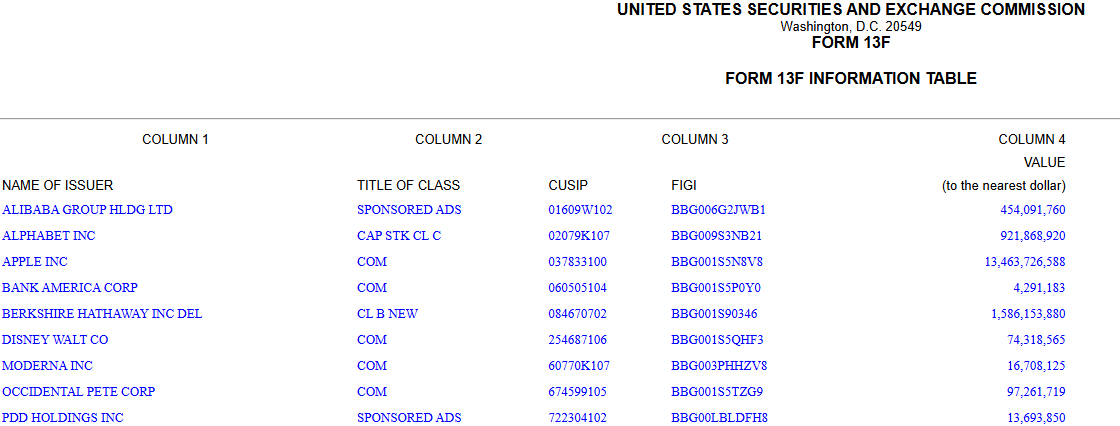

In 2023, he finally bought a position in Nintendo. He increased his PDD position over time, and holds Buffett-style and tech stocks: Apple (constituting 80% of the H&H portfolio), Berkshire Hathaway, Bank of America, Google...

His biggest buys this year have been Alibaba and Occidental Petroleum, a Burry and a Buffett pick respectively.

The successors to BBK each went on to make their own history. By 2016, Vivo and Oppo became the #2 and #3 smartphone vendors in China behind only Huawei, both entering the top 5 globally. BBK group sold 39 million units that year.

Within a couple of years, together with brands like Oneplus, realme and IQOO, the BBK group captured over 40% of the Indian smartphone market…

‘A happy life is the fundamental objective’

— Duan Yongping

Duan often described himself as having ‘no great ambition’, and appeared to be engaged in the pursuit of happiness.

Remarkably, Duan literally worked to provide entertainment: from gaming consoles, VCD and DVD players, to smartphones (via BBK subsidiaries).

As chairman, he still visited BBK companies each year, but mostly to meet up for golfing sessions rather than calling the shots.

Both Oppo and Vivo still make extensive use of employee equity incentives, just like Duan. Employees hold over 60% of the total shares for each, making the ownership mindset quite literal; turnover among management has been low.

However, the two are separate entities and competitors. In fact, they are similarly positioned and cater to the same core group of customers. Somehow, under Duan’s influence they are still able to co-exist rather peacefully.

On Duan’s investing

‘I don’t tell people what to do, because it’s impossible to teach, so I always tell people what not to do… for example, even aged seven or eight, I was climbing hills to chop down trees and rearing pigs, how do you imitate that?’

— Duan Yongping

Having a natural style of investing that is consistent with his life philosophy and experiences, Duan is not the easiest investor to emulate for multiple reasons:

Outsourcing. Unlike many value investors, Duan does not go through financial reports in detail, but taps the BBK investment team for research

Focus on culture. Honed by experience, Duan’s ability to detect a healthy culture is sharp, yet it cannot be easily specified for replication

Extreme patience. He took his sweet time (nearly a decade!) to figure out Apple, could tolerate multiple drawdowns of up to 55%, and still keep buying

High concentration. Duan believes it hard to keep up with too many companies, and if Buffett could only do 10 or so, he would only be able to handle 2 or 3

Compounding the difficulty is that Duan still occasionally make exceptions, for example when he invested in PDD purely because he had great trust in Colin Huang.

The outsourcing makes it harder for retail investors to emulate, while concentration, drawdowns and long horizon makes it harder for many institutional investors.

Duan does offer some general principles:

Be long-termist. For Duan, even 5 years would struggle to be defined as long-term; he focuses on valuation over timing, dislikes trying to predict stock prices, and often adds when stocks go down, yet is relatively quick to cull mistakes

Buy what you know. Only invest in what is understood and researched; Duan invested in NetEase because he played their games and knew the founder

Only invest what you can afford to lose. Duan’s emphasis on doing what he enjoys meant that it is important to only invest what can be safely lost - otherwise it becomes no longer enjoyable

‘Only when you do what you like, can you inspire your full potential and enjoy the process’

— Duan Yongping

Duan does usually not look at financial metrics in isolation, but assesses the business holistically, using them together for a more complete picture.

Note that he does not use hard absolute criteria, but more in relative terms to understand, compare and select for a single winner in a sector, which would ideally have strong pricing power and low replaceability.

Return on equity (RoE). His views on RoE changed over time. Duan uses it to remove unattractive businesses, after which he looks at the debt. If debt levels are OK, he would assess the company culture to see if profits are sustainable

Gross margins (GM). Past deals had high GM at time of investment, like Apple at 60% and Moutai at 90%; yet he warns high GM alone do not guarantee profitability

Net margins (NM). Apple typically remained above 20%, and Moutai above 40%, but again no hard and fast rules

Price to earnings (P/E). His investments usually have P/E ratios under 20x, but there are notable exceptions, such as NetEase which was lossmaking at the time

Margin of safety (MoS). He aims for a deep MoS of 50% or more

In terms of risk management, Duan’s rules are simple.

No false diversification. Duan likes concentration but is against having multiple holdings in the same sector - he goes long on the leaders only

No shorting. He added this rule after having been burned by shorting Baidu

No leverage. The drawdowns would cause his portfolio to blow up if levered

Coda

The ‘do the right thing’ culture Duan had instilled held firm beyond his retirement.

‘If it is not right, do not do it, if it is not true, do not say it’

— Marcus Aurelius

Vivo maintains a rule of not speaking ill of competitors or actively commenting on them in public. If prodded for an opinion, their CEO’s typical response would be the aspects worthy of respect of rivals.

Back when brainstorming for the brand name for their first game console at Subor, Duan favored ‘Micro Genius’, yet it was already taken. BBK’s offer of CN ¥3 million ($360k) to buy the brand was also turned down.

Some readers may recognize this famiclone brand, the manufacturers of which also made other models with names such as ‘Creation’, ‘Pegasus’, ‘Bitman 2’ and ‘Spica’.

In 2007, Jin became the new BBK Educational Electronics CEO, succeeding Huang, who had succeeded Duan. During the GFC, he learned that the owner of ‘Micro Genius’ had divested of an unrelated brand, and sensed that they may be short of cash.

It took the consultancy he hired over half a year to find the owner overseas. Down on his luck, the businessman asked for only CN ¥300k ($44k - the yuan had appreciated), remarking that he had rejected BBK’s offer of ten times as much over a decade earlier.

The consultancy quickly signed the contract and completed the purchase on behalf of BBK.

Only many months afterwards did Jin learn of the final price. Much surprised, he immediately felt that this was not right. Instead, Jin arranged for another CN ¥2.7 million to be sent to the previous owner, along with a short message.

‘We are actually the same BBK from years ago; we believed your brand was worth 3 million then, and we believe it’s still worth 3 million now’

— BBK

Disclaimer: This should not be construed as investment advice. Please do your own research or consult an independent financial advisor. Alpha Exponent is not a licensed investment advisor; any assertions in these articles are the opinions of the contributors

Duan, Charlie and Li Lu

Great role models and heroes to have