Others invest for a living, he does so for fun.

He was born to a family living in acute food insecurity, and failed his college entrance exams the first time round.

His first job paid less than $25 — per month.

He went on to found his own company at the age of 34, and gave it up to retire early as a multimillionaire at 39 — for the love of his life.

Then he took up investing as a pastime in addition to golf after coming across Buffett’s teachings, picking up a 100-bagger, investing in Apple 6 years before Buffett bought of his Apple holdings, and becoming a billionaire along the way.

Ever enigmatic, the true extent of his wealth is unknown. Thanks to his investments, however, it is likely his net worth now stands north of at least CN ¥100 billion. If so, it has also 100-bagged in a little over two decades, or over 23% p.a. for the period.

Nowadays, one out of every six phones sold (Oppo, Vivo, OnePlus, Realme, IQOO…) globally traces its lineage back to the company that he founded, yet his name remains unknown to many. His mentees include the man behind PDD and Temu, Colin Huang.

‘Duan has had a tremendous impact on me. Of the generation after him … I’m his fourth apprentice.’

Colin Huang, founder of PDD

Despite still being one of the most influential businessmen in China, Duan now lives in the US, spending his time golfing, donating billions to his favorite causes, investing and sharing his insights on social media.

Unlike Buffett, Duan is a growth-value investor, and does not shy away from tech if he sees value. Above all else, he seeks joy. Let us see if his experiences can help us find our inner Duan.

Duan was born in 1961 in Jiangxi, one of the poorer provinces of China, towards the tail end of three years of famine.

Millions starved to death.

Fortunately, his parents found employment that same year with a university in the provincial capital, Nanchang (there was generally more food in the cities).

Rather less fortunately, only five years later, the family was sent into rural Jiangxi for ‘re-education’ as the Cultural Revolution began.

Jiangxi is rice country, and rice is extremely labor-intensive. Even as a kid, Duan had to join in the rice-planting and harvesting. On top of this, every day he trudged miles over the hills to cut firewood. Despite the hard labor, the family often went hungry.

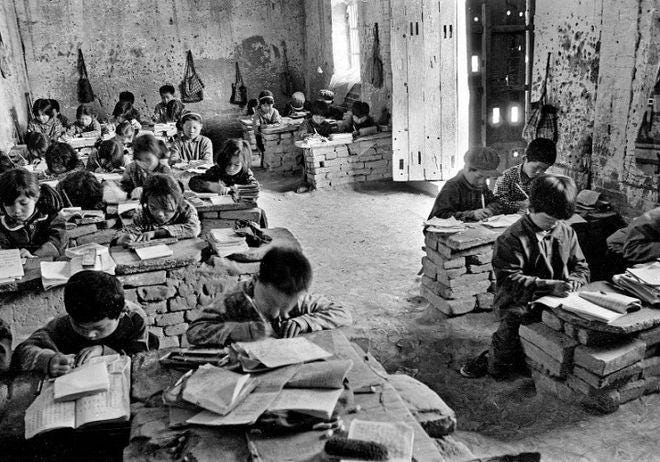

Duan’s elementary school hodgepodged together students of different grades in ramshackle classrooms. Conditions were difficult.

Duan was not a stellar student; instead of studying, he liked to spend his time with friends, catching fish in the river and throwing rocks at birds … and windows.

After he graduated high school, however, a life-changing reform reshaped life for him and 5.7 million others.

In 1977, China re-introduced the college entrance examination. Previously, university students were selected by a political committee, but thereafter, only marks mattered.

Duan eagerly signed up.

He flunked, hard.

The university admission rate was 4.8% (incidentally, the same as MIT’s acceptance rate for the class of 2026). But across the four subjects examined, Duan managed an average score of only a little over twenty percent.

But he knew the opportunity was too good to pass up. A quirk in timing had the 1977 and 1978 exams only half a year apart. Duan buckled down and speedran through the entire high school curriculum in five months.

‘I feel it was at that time I discovered I was pretty good at studying. Before I just didn’t study very much, but then within this short period I felt it was rather interesting and satisfying, and this particular experience was extremely impactful on my life’

— Duan Yongping

It was arguably Duan’s first multi-bagger.

This time, he averaged more than 80% over the five subjects of the revamped exam - a four-bagger in less than half a year, putting him in the top 0.2% of test-takers.

He was the only one in his high school to gain admission to university, and he had made it to one of the top ten in the country, Zhejiang University.

As he held the offer letter in his hand though, he felt lost. Subsequently, he muddled through years of university, only realizing as he was about to graduate why he was not happy.

‘Why was I not happy? Because I had no goal … The joy of life is in the process, not in the result. So I’ve told many people, if you want to be happy, you need to never stop having a reasonable goal. Don’t set a goal to be the president, which is neither here nor there, and you have no way to achieve it, that won’t motivate you! So a goal must be reasonable.’

— Duan Yongping

Duan was accepted to the Department of Wireless Electronics, which later evolved into the Department of Electronic Engineering and Department of Computer Science, giving the young Duan an exposure to technology.

Yet as others around him aimed for careers in research and academia, Duan soon felt he was not cut out for this path.

Like Steve Jobs who dropped out of Reed College, Duan only attended classes that he found interesting. Perhaps it was not a coincidence that the two eventually both became titans of the smartphone industry.

‘The diploma isn’t at all important to me. What’s important is whether I can gain solid and applicable knowledge.’

— Duan Yongping

One would not have easily surmised this, however, from Duan’s first interaction with a telephone. Even after a quarter of an hour, he could not figure out how to work the machine, only learning how to make a call by observing someone else.

Following graduation in 1982, due to China’s then planned economy, Duan was placed into a well-regarded SOE in Beijing, Factory #774.

He was paid a monthly salary of less than CN ¥50, or just under $25 at the time.

Others felt he was set for life.

But Duan had different ideas. He saw how his colleagues planned for retirement despite only being in their early twenties, and felt bored out of his wits.

Factory #774 was at one stage the largest vacuum tube producer in Asia, but by Duan’s time, it was deep in decline as orders from the military fell.

Many years later, a colleague who joined around the same time as Duan privatized Factory #774 to become BOE Technology Group, now a leading display manufacturer.

After toughing it out for three years, Duan left to read Econometrics in Renmin University, another eminent institution in Beijing.

Although he initially went to Beijing with the aim of staying there long-term, Duan found the city too stifling. The local culture greatly respected officials and authority figures, which Duan felt uncomfortable with, being born into a poor, provincial family.

So despite finding another job in Beijing, he turned down the offer and thought about heading elsewhere. Duan wanted to map his own journey.

The price was his Beijing hukou (in effect a Beijing residency), which he had to forgo. It allowed registered residents many social benefits including preferred access to education, healthcare, housing, employment, etc. Some valued it as much as CN ¥10,000 — or around two decades’ gross mean salaries in Beijing.

Duan joked that he could buy it back for that amount if he needed it. His formative experience during the college entrance exam gave him a resolute confidence.

‘Going through the college entrance exam, I felt that as long as I can find what I truly want to do, I should be able to do it. And after all these years, I found that it was really the case, if you give it your all, actually it’s hard not to succeed!’

— Duan Yongping

He had already enjoyed a taste of small-time capitalism, flipping hair tonic as a master’s student. Duan was hungry for more and saw his edge as a student of economics to be in Guangdong, where reforms created burgeoning markets.

After he made his decision, he departed Beijing immediately, without even bothering to submit his graduation thesis.

Aged 27, Duan made his way alone to Foshan, a bustling city close to Guangzhou. There a company hired over 150 bachelor’s and over 50 master’s degree holders.

Duan soon left.

He realized that the business owner did not particularly respect talent. Moreover, among such a crowd of well-qualified peers, it was difficult to stand out without a proven track record. But this meant that he would not easily be given the opportunities to grow and build such a record, a catch-22.

The road less traveled — Duan was unafraid to repeatedly pass up seemingly good opportunities to seek areas where he had a clear edge, even if not as conventionally attractive

A friend introduced him to Yihua Group, one of the largest companies in Zhongshan, another city in Guangdong. There the GM of Yihua soon spotted his potential and put him in charge of the struggling Rihua factory, which produced video game consoles.

It was hemorrhaging cash.

The factory lost over CN ¥2 million in 1988 (around $540k, the yuan had devalued significantly from a few years earlier), and had only a little bit more than CN ¥3,000 (around $800) in cash left.

A dozen or so employees remained and reported to Duan, who was the plant director and all of 28 years old.

He revamped the incentive system to reward star employees and push out underperformers, but knew they needed to work out how to improve profitability, and for that, they needed to have a good product.

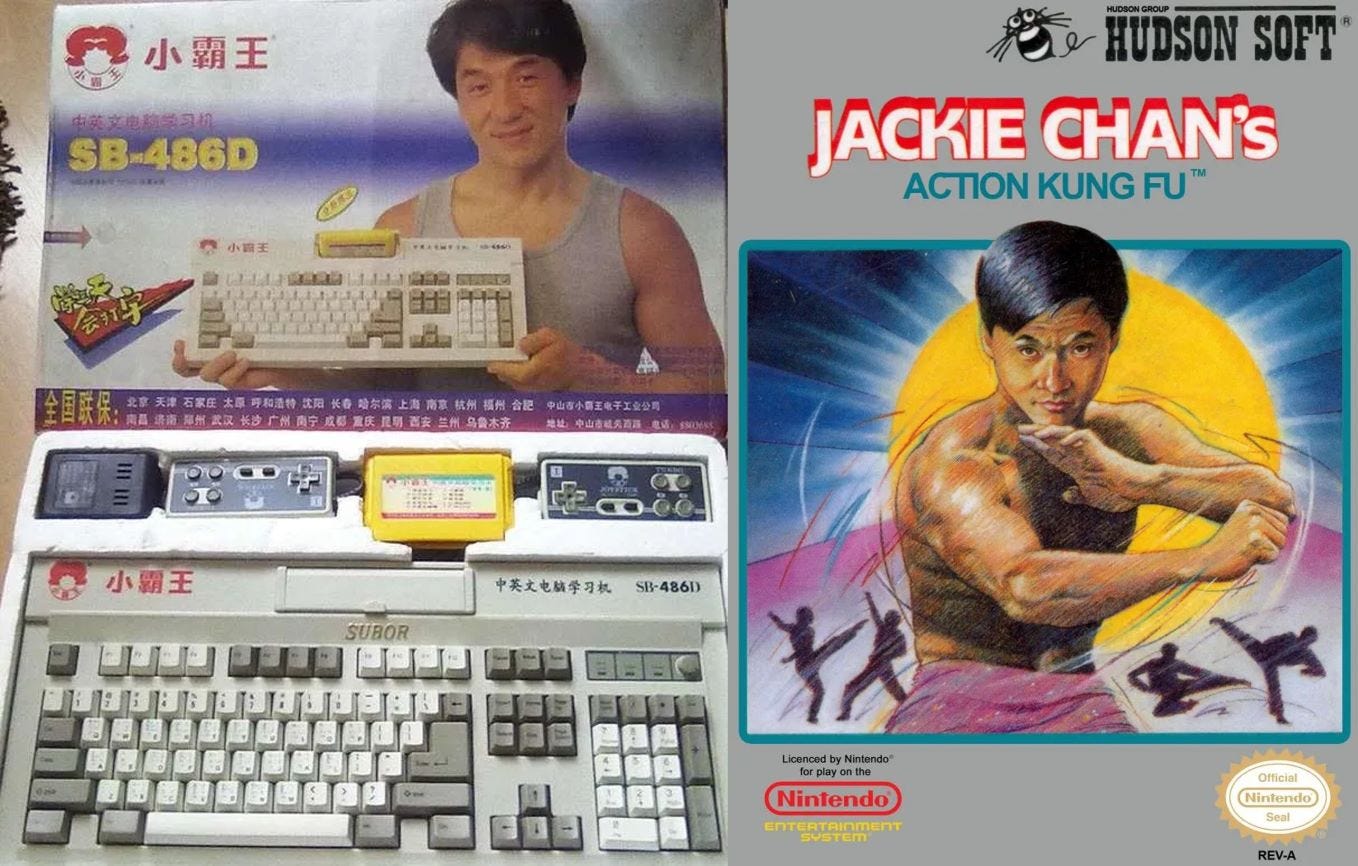

At the time, Nintendo’s Famicom was selling like hotcakes in Japan and North America, where it was known as the NES.

Many Asian and Eastern European consumers could not afford a Famicom, however, so an entire cottage industry of famiclones - machines that offered compatibility with Nintendo cartridges - sprung up. Here Duan saw a strategic opening.

As an electronics OEM originally making knockoff Walkmans, Rihua’s margins were unsustainably thin. Yet though demand for famiclones rocketed, there was no guarantee of profitability: competitors numbered in the dozens if not hundreds.

Duan figured having a differentiated brand would allow him to capture a greater share of the profits, so he licensed the ‘Creator’ brand of famiclones from Taiwan.

Early results were promising.

Seeing this, the owners of ‘Creator’ promptly licensed the brand to other competitors, without informing Duan, who only learned about it afterwards.

Incensed, Duan decided to create his own brand.

Xiaobawang, or Subor, was the result.

Duan undertook a holistic approach to brand building, enhancing build quality and betting big on marketing, yet all the time maintaining cost-effectiveness.

While perhaps one in four consoles were defective for some competitors, Subor’s kept the defect rate under 2%, even as they scaled volumes. This also meant that they could afford to provide a quality aftersales service, further enhancing the brand image.

Meanwhile, Duan showed off his marketing chops, splashing out CN ¥400k (around $80k) for a commercial on primetime CCTV, the Chinese state-owned TV channel, which had a viewership of hundreds of millions.

This was big money, almost a hundred times the $1k cash they had left in their bank account only a short while prior. Luckily, the investment was to pay off handsomely.

Their console was priced at around $35, much lower than a full-price Famicom, which went for from $90 for a Basic Set NES in the US, to over $170 for a Super Famicom in Japan. For context, the average urban household in China then had a disposable income of $300 per year, and rural households pulled in less than half this figure.

As 1991 drew to a close, sales exceeded CN ¥100 million ($19 million), profits hit CN ¥8 million ($1.5 million), and Duan was ready for the next step.

Many Chinese parents did not look favorably on video games, seeing them as a distraction from studying. But again Duan saw an effective strategic positioning.

What if … they could be used for learning?

We need to backtrack a little here.

Written Chinese did not have an alphabet; instead it used thousands of characters.

The natural idea was to use a key for each character. Japan did so for Kanji, but for even 1,000 characters multiple large keyboards had to be used, and it was hard to find or remember where any given character was, making it impossible to type quickly.

This problem was worse for written Chinese, which had more than 3,000 commonly used characters. Keyboards with a key for each character ended up being the size of dining tables.

The lack of a viable input method throttled progress, and the PC revolution was passing China by. But then a programmer surnamed Wang played an unlikely role.

Born into a family of farmers, Wang had a knack for technology. He worked in the civil service as a scientific consultant, and was dissatisfied with a phototypesetting machine for Chinese imported from Japan. He took on the challenge to do better.

A keyboard would be a distinct improvement, and as we know, the real bottleneck was the encoding: how to devise a memorizable series of keystrokes for each character. Evidently, they had to conform to some patterns.

It took much trial-and-error and many talks with other experts to find the right approach.

Wang copied each of the over 13,000 characters from his dictionary onto separate sheets of paper, where he decomposed them into radicals (parts of characters).

Each character would then be represented by a combination of these radicals, much as they are written.

The first iteration resulted in over 600 radicals, which meant more than 600 keys would be needed —far too many. Wang set about further merging groups of radicals to drive this number down and gathered a small team about him.

Each merge meant the characters had to be re-encoded and remapped. There was also the challenge of collisions — when the same keystrokes might map to multiple characters. These had to be carefully disentangled, often forcing alternative schemes.

Eventually, Wang invented a fast way of identifying collisions, laying out characters in enormous matrices on translucent sheets of paper (like slide transparencies). Stacking them together with a light beneath showed up any collisions immediately, saving them from sifting through the over 10,000 sheets of characters1 to look for matches.

They subsisted on bread and pickles to eke out the $1,800 grant that had to last the project.

After half a decade and 120,000 sheets of paper, they finally mapped all 13,000 characters to a standard QWERTY keyboard through ingenuity and sheer force of will.

Wang then coded up the software to enable its use on computers, and in doing so created the first Chinese killer app, the Wubi input method.

Wubi has a steep learning curve, but once mastered, was fast. The speed record was more than 300 Chinese characters per minute (chpm) over ten minutes, roughly the equivalent of 200 English words per minute. Even casual users could manage 60-80, about three times the speed that was possible before its invention.

Wang dedicated most of his life to driving Wubi adoption, and it eventually captured over 90% market share at peak.

Duan strategically used the alpha from the hard work of others, and built on top of that, greatly increasing his own chance of success; a key requirement in investing

Parents wanted their children to learn Wubi to be able to use computers, yet personal computers then were much too expensive for most Chinese families, and expensive was a problem Duan knew exactly how to solve.

He married a console chip to a basic computer system, and also developed and bundled together a game to help master Wubi typing. The result was not dissimilar to a SC-3000 from Sega, which lost out to the Famicom in Japan.

Other software to help learn typing English, the language itself and coding were also developed and sold.

Just as Jobs and Apple played a major part in the PC revolution a decade-and-a-half earlier, so did Duan and Subor. By a twist of fate, Subor even used a variant of the same chip as the Apple I and II - the legendary MOS 6502, invented in the US in 1975.

This positioning as Subor ‘learning machines’ allowed families to justify to themselves the purchase. Of course, they still supported games cartridges, and once the parents were away…

To drive awareness, Duan hired Jackie Chan to endorse the brand. Though it may have seemed exorbitant for a cost-centric business as Subor to hire Jackie Chan, one of the highest-compensated movie stars in Asia, Duan had a clear logic.

‘With Jackie, someone might see the commercial say 3 times and remember the concept [of learning machines]. Without him, it might take 8, 9, 10 or more times and they still won’t remember… We paid Jackie less than 10% of our total marketing spend, just several percent… Why do I say it’s cheap? If Jackie’s presence could raise the memorability or favorability of the ad by several percentage points, it would’ve been worth it. But if you think about the impact, it is definitely more than several percent’

— Duan Yongping

By 1993, Subor’s sales reached CN ¥200 million ($35 million), and more than doubled this figure the year after, taking 80% share of the Chinese ‘learning machine’ market. The following year, sales more than doubled again to exceed CN ¥1 billion ($175 million).

Duan succeeded in bringing about a PC revolution of sorts in China, and Subor had become a household name. Both were richly rewarded.

Then Duan quit.

We shall continue with Duan’s story, including his investments and teachings on investment in the next installment of this series.

Disclaimer: This should not be construed as investment advice. Please do your own research or consult an independent financial advisor. Alpha Exponent is not a licensed investment advisor; any assertions in these articles are the opinions of the contributors

Edit: clarification - Duan invested in Apple 6 years before Buffett bought most of his Apple holdings in 2017 - though Buffett initiated a small position in 2016

Our knowledgeable readers may note parallels between the Wubi scheme and the hashtable, an important data structure in computing. It is also remarkable how Wang’s technique for spotting collisions utilizes similar underlying principles to the Lunometer, invented by Luhn, who also invented the hashtable.

"The diploma isn’t at all important to me. What’s important is whether I can gain solid and applicable knowledge." — Duan Yongping

"I have never let my schooling interfere with my education." - Mark Twain